Setting 1.5°C compatible wind and solar targets

Authors

Neil Grant, Gustavo de Vivero, Tina Aboumahboub, Markus Hagemann, Fadil Razak, Emily Daly, Severin Ryberg, Lara Welder

Share

At COP28, the world committed to tripling renewable capacity by 2030. This represents a key action that governments can take to cut emissions in line with the 1.5ºC warming limit. All countries are also called upon to submit new 2035 climate targets by early next year.

Providing ambitious targets, including for wind and solar rollout, can help turn the tripling goal into action and close the gap to 1.5ºC , while also achieving universal electricity access by 2030.

To help guide national target setting, we have produced 1.5°C compatible wind and solar benchmarks for 11 key countries, responsible for over 70% of global wind and solar deployment. As wind and solar will be the backbone of the energy transition, setting specific targets for them could become the defining policy action in global efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C.

Key findings:

On average, wind and solar capacity needs to grow five times by 2030, and eight times by 2035, to align with 1.5ºC.

To close the renewables capacity gap in 2030, countries need to install on average three times more wind and solar a year over 2023-2030 compared to the average pace achieved since 2020.

While solar grows faster than wind, wind provides more electricity than solar across the 11 countries until the mid-2030s. By 2050, solar provides around half of total electricity generation, and wind around a third.

National results

There is no single way to translate global goals to the national level. A country’s wind and solar rollout depends on a range of factors, including forecast electricity demand, the pace of fossil phase-out needed, the availability of other renewable technologies like hydropower and geothermal, and the split between wind and solar. The benchmarks presented here offer one interpretation of global targets translated to the national level, drawing from both global and national evidence to capture the key factors mentioned above.

Country briefings are available for Australia, Brazil, China, Germany, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, South Africa, Türkiye, and the US.

India is set to more than triple wind and solar capacity by 2030 compared to 2022 but would need further international support, including climate finance, to scale five-fold to over 600 GW to meet growing demand and move away coal dependence in line with 1.5°C.

Indonesia is only just beginning the transition to wind and solar. To meet future electricity demand while phasing out coal power, almost 110 GW of wind and solar would be needed by 2030, with the majority of this coming from solar. International support will be critical to delivering this.

Mexico’s power sector transition has faltered in recent years, as policy support has shifted from renewables to fossil gas. To get back on track and align with 1.5ºC, around 80 GW of solar and 20 GW of wind would need to be installed by 2030. Current rollout is far behind this rate and needs accelerating.

Brazil would need to reach almost 140 GW of wind and solar by 2030 to align with 1.5ºC. Brazil’s current pace of wind and solar deployment puts it well on track to achieving this benchmark. As such, investments in fossil gas power stations represent a needless economic and climate risk.

Türkiye would need to reach just over 90 GW of wind and solar by 2030 to align with 1.5ºC. This would be equivalent to achieving the 2035 targets set by the National Electricity Plan five years early. By 2035, 120 GW of solar and 30 GW of wind would be needed to align with these benchmarks.

Germany’s targets for renewables rollout in 2030 are broadly aligned with 1.5ºC, and could help phase out of fossil fuels in the power sector. The government should make a clear commitment to fossil-free power by 2035 and would need over 500 GW of installed wind and solar capacity to achieve this.

South Africa would need to reach almost 70 GW of wind and solar by 2030 to align with our benchmarks. Shifting away from an ageing and unreliable coal-fired fleet could help meet South Africa’s electricity needs, while also cutting emissions in line with the Paris Agreement. International support, including via the JETP, can help catalyse this transition.

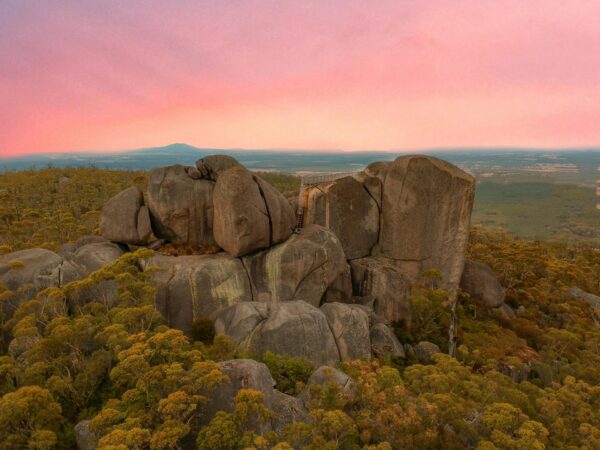

Australia’s wind and solar generation under current policies is set to grow 2.5 times by 2030, but it would need to grow four to five times by 2030 from 2022 to align with 1.5˚C. Almost 170 GW of wind and solar capacity would be needed by 2030.

Nigeria has abundant wind and solar potential, but investment levels would need to scale up considerably to meet our benchmarks. International support, including concessional and grants-based finance, will be crucial. To meet electricity demand growth while reducing reliance on diesel and gas in the power sector, over 50 GW of wind and solar would be needed by 2030.

China needs to reach 4.5 TW of wind and solar by 2030 to align with 1.5°C. This is needed to meet rapidly growing electricity demand in China, and to also displace large volumes of coal on the road to fossil-free power by 2040. The rollout of solar is broadly on track with 1.5ºC in China, but wind deployment needs to accelerate further.

The United States needs to grow wind and solar capacity almost five times by 2030, reaching almost 1400 GW of installed capacity in the central benchmark presented here. The Inflation Reduction Act is helping to accelerate wind and solar deployment, but more would need to be done to ensure that the United States achieves its target of a clean power sector by 2035.