The Paris Agreement is working. Ten years later, the world needs to finish the job.

Whether the Agreement ultimately succeeds depends on whether political leaders and their governments have the courage to close the ambition gap, phase out fossil fuels, scale up finance for a just transition, and protect people already facing mounting loss and damage.

Share

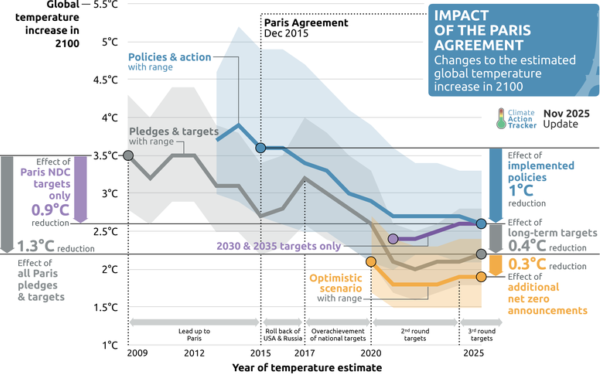

Ten years ago in Paris, the world did something extraordinary. Governments agreed to limit warming to 1.5°C and to get global greenhouse gas emissions to net zero in the second half of this century. Since then, countries have adopted policies and targets that would bring projected warming down to roughly 2.6–2.7°C–about one full degree less than what was expected before Paris.

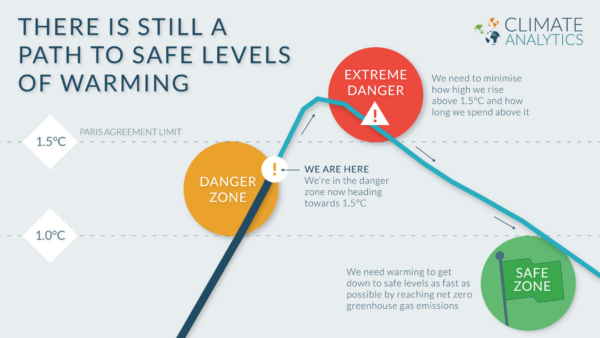

One degree sounds small. It isn’t. A world that peaks as close as possible to 1.5°C and returns below it rather than racing toward 3–4°C means fewer deadly heatwaves, less sea-level rise, less damage to crops and water supplies, and a lower risk of crossing irreversible tipping points. The IPCC has shown that 1.5°C versus 2°C could mean about 10 million fewer people exposed to sea-level rise, less biodiversity loss, and significantly lower risks to health, food and water security. For the most vulnerable countries and communities, 1.5°C isn’t a nice-to-have. It’s a lifeline.

The Paris Agreement has already reduced future harm, but progress has slowed and it has not yet made us safe.

Paris rewired how we think about climate

The Paris Agreement and its targets, along with the policies and actions countries have taken, helped to reshape markets and institutions.

Global investment in clean energy has surged since 2015. Around the time Paris was signed, fossil fuels still attracted more investment than renewables. By 2023, each dollar going into fossil fuels was matched by about $1.70 for clean energy; today, clean technologies attract over $2 trillion a year – around twice fossil fuel investment. This is Paris in action: the Agreement sent a long-term signal that is helping to pull capital into clean technologies and away from fossil fuels.

Thousands of companies and financial institutions have adopted “science-based” or net-zero targets, many explicitly aligned with 1.5°C pathways. Climate disclosure has exploded: nearly 25,000 firms now report through CDP alone, covering around two-thirds of global market capitalisation.

The Paris targets have also filtered into law. The International Court of Justice recognised the 1.5°C limit as a legal obligation, confirming that governments have duties not just to cut their own emissions, but also to regulate private actors and rein in fossil fuel expansion.

Paris progress stalls

But in recent years, political will has wobbled. The latest Climate Action Tracker update finds that projected warming under countries’ targets is stuck at about 2.6°C – essentially no progress in warming outlook for four consecutive years. Many governments have delayed strengthening their 2030 targets, even as climate impacts – from fires and floods to record heat – have surged. The Paris Agreement bent the curve, but momentum has stalled just when it needs to accelerate.

That’s where the Paris Agreement’s commitment to the “highest possible ambition” really matters. Under Paris, countries aren’t just invited to do a bit better each time; they are expected to put forward the strongest effort they can reasonably make, given their capacities and responsibilities. For major emitters, that means using today’s cheaper renewables, plummeting battery costs and maturing technologies as a springboard to go further and faster, not as an excuse to coast.

Even after years of under-delivery, new analysis shows it is still physically and economically possible to bring warming back well below 1.5°C by the end of this century – if countries finally live up to that “highest possible ambition” promise.

A new Climate Analytics and PIK study, Rescuing 1.5°C: new evidence on the highest possible ambition to deliver the Paris Agreement maps a Highest Possible Ambition (HPA) scenario: warming peaks at around 1.7°C before mid-century and then falls to roughly 1.2°C by 2100, bringing us back well below 1.5°C.

In the HPA scenario, global CO₂ emissions reach net zero before 2050, and total greenhouse gas emissions hit net zero in the 2060s – earlier and deeper than in the IPCC AR6 pathways.

To achieve this outcome, power, transport and much of industry are rapidly electrified so that by 2050, nearly two-thirds of all energy demand needs to be met with clean electricity.

Fossil fuels are pushed out of the system, with a fossil-free global economy achievable by around 2070 and advanced economies getting there by 2050. Methane emissions need to fall sharply – 20% by 2030 and 30% by 2035 compared with 2020 levels, with energy-sector methane more than halved this decade.

Carbon removal – particularly technology-based removal - will need to be scaled up to help bring temperatures back down from peak levels and reduce the duration of overshoot.

This is a tough ask, but notably, our analysis finds that even if carbon removal rolls out at only about half the speed assumed, the world could still get temperatures back below 1.5°C by the end of the century – provided we slash fossil fuel use and other emissions fast enough.

The next decade will decide Paris’s legacy

Ten years on, we can say that Paris is working – it has got the world about halfway towards 1.5C, from the 3.5-3.6C projected in 2015. But action is just not fast enough.

The Paris Agreement has bent the curve of future warming and has sent the signals that have begun to rewire the global economy. It has anchored the 1.5°C limit in science, law and finance, and mobilised a wave of action that almost certainly would not have happened otherwise.

But the Agreement is a bottom-up framework, and relies totally on the level of ambition put forward by each and every country.

Whether the Agreement ultimately succeeds now depends on whether political leaders and their governments have the courage to use the Paris Agreement to finish the job: closing the ambition gap phasing out fossil fuels rather than expanding them, scaling up finance for a just transition, and protecting people already facing mounting loss and damage.

Paris has shifted our trajectory. Now, the real bottleneck isn’t science or technology; it’s political courage and will to stand up to fossil fuel industry.