Developing countries need support adapting to deadly heat

Fahad Saeed and Bill Hare

Many vulnerable people in South Asia are already struggling to protect themselves from unbearably high temperatures – which are set to worsen.

Share

This article was first published on Climate Home News on 30 May 2024.

Pakistan’s southern province of Sindh has been sweltering under 52°C heat in recent days. Not in the news however is that wet-bulb temperatures in the region – a more accurate indicator of risk to human health that accounts for heat and humidity – passed a key danger threshold of 30°C.

Climate change is increasing the risk of deadly humid heat in developing countries like Pakistan, Mexico and India, and without international support to adapt, vulnerable communities could face catastrophe.

What is wet-bulb temperature?

Wet-bulb temperature is an important scientific heat stress metric that accounts for both heat and humidity. When it’s both hot and humid, sweating – the body’s main way of cooling – becomes less effective as there’s too much moisture in the air. This can limit our ability to maintain a core temperature of 37°C – something we all must do to survive.

A recent study suggests that wet-bulb temperatures beyond 30°C pose severe risks to human health, but the hard physiological limit comes at prolonged exposure (about 6-8 hours) to wet-bulb temperatures of 35°C. At this point, people can experience heat strokes, organ failure, and in extreme cases, even death.

Climate change and deadly heat

Globally, around 30% of people are exposed to lethal humid heat. This could reach as much as 50% by 2100 due to global warming. To date, the climate has warmed around 1.3°C as a result of human activity, primarily due to the burning of fossil fuels. And along with the extra heat, with every 1°C rise the air can hold up to 7% more moisture.

A comprehensive evaluation of global weather station data reveals that the frequency of extreme humid heat has more than doubled since 1979, with several wet-bulb exceedances of 31-33°C. Another recent study predicts a surge in the frequency and geographic spread of extreme heat events, even at 1.5°C warming.

What this shows is that the humid tropics including monsoon belts are all careening towards the 35°C threshold, which is very worrying for countries like Pakistan. The city of Jacobabad has already breached 35°C wet bulb temperatures many times. More areas of the country are likely to be exposed to such life-threatening conditions more often due to climate change.

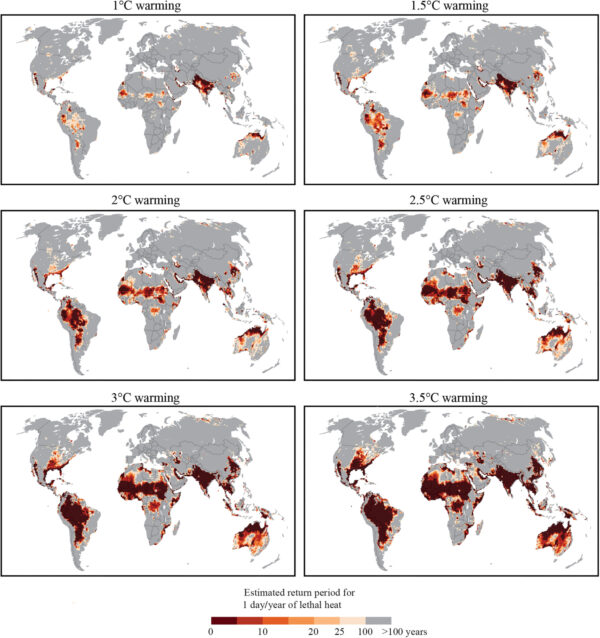

At 1.5°C of warming, much of South Asia, large parts Sahelian Africa, inland Latin America and northern Australia could be subject to at least one day per year of lethal heat. If the world gets to 3°C, this exposure explodes, covering most of South Asia, large parts of Eastern China and Southeast Asia, much of central and west Africa, most of Latin America and Australia and significant parts of the southeastern USA and the Gulf of Mexico.

Areas of the world that will experience at least one day of deadly heat per year at different levels of warming

Even at 1.5°C of warming, there will be high exposure to lethal heat in large regions where billions presently live. This terrible threat to human life calls for urgent action to limit warming and help at risk communities adapt.

Adapting to hard limits

While 35°C can prove deadly, one study suggests a 32°C wet-bulb threshold as the hard limit for labour. More realistic, human-centred models found this overly optimistic, as direct exposure and other vulnerability factors were ignored. Vulnerable groups including unskilled labourers would be most at risk of losing their income.

In densely populated urban centres, lethal humid heat is not just a future projection but a current reality. This calls for urgent adaptation measures which integrate the risk of deadly heat into urban planning, public health, early-warning systems and emergency response.

Investments in green spaces, heat-resilient buildings and urban cooling are vital adaptation strategies. Community initiatives like awareness campaigns, indigenous cooling strategies and local heat action plans are also essential. Households could consider investing in cooling technologies or migrating – options mostly available to the wealthy.

As climate change makes lethal humid heat a growing threat in some of the world’s most populous areas, more attention must be paid to understanding its risks – especially in vulnerable regions with huge data gaps. This demands a multidimensional response that combines scientific research, policymaking and community engagement.

The potential scale and level of risk to human life also reinforces the importance of ensuring that the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C global warming limit is met. To do this, we need to halve emissions by 2030. Countries should therefore strengthen their 2030 emissions targets in line with the warming limit as they prepare equally ambitious 2035 targets in updated NDCs.

The Pakistan heatwave is a terrible reminder of this often-underestimated threat. We must act now to limit warming while we adapt to the growing danger of deadly heat if we are to avoid potentially wide-reaching tragedies in the future.