Troubled waters: risks and realities of blue carbon in climate action

Authors

Blue carbon has rapidly risen up the climate agenda as countries seek new pathways to meet and enhance their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Once a niche scientific topic, the carbon stored in coastal and marine ecosystems, such as mangroves, salt marshes, and seagrass meadows, is now viewed as a potential bridge between mitigation, adaptation, and climate finance. Yet, many uncertainties persist in the science, policy, and governance foundations necessary for the responsible use of blue carbon. The level of effort in this area must also reflect the very limited global mitigation potential of blue carbon ecosystems, estimated with large uncertainties as approximately 2% of 2024 global annual GHG emissions (3% of global fossil CO2 emissions).

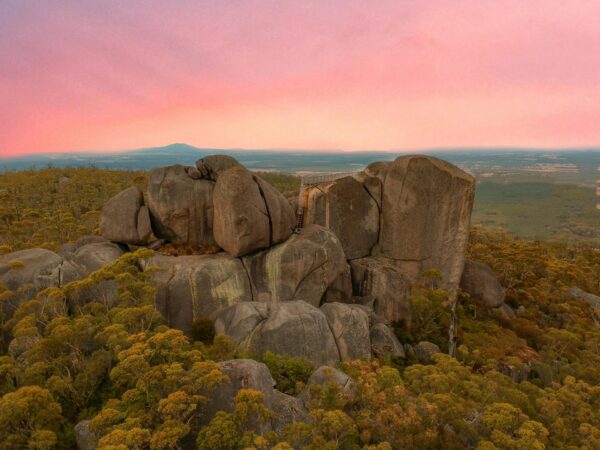

This brief reexamines blue carbon at a time when the world has warmed by about 1.4°C and climate tipping points are being approached or exceeded. Associated climate changes threaten the persistence of the very ecosystems positioned as carbon sinks. While blue carbon systems can store carbon for centuries, their permanence depends on stable ecological and climatic conditions that are rapidly eroding. Disturbances such as sea-level rise, erosion, marine heatwaves, and extreme storms can quickly reverse sequestration gains, transforming these sinks into sources.

Scientific advances have clarified both the potential and fragility of these systems. Blue carbon ecosystems remain vital sinks in the earth system, and the protection of intact ecosystems delivers immediate, verifiable climate and resilience benefits. However, uncertainties and risks persist around the role and viability of the ecosystems, in particular for offsetting purposes. New evidence suggests that blue carbon ecosystems may cease functioning as net sinks beyond 1.5°C of warming, underscoring the urgency of deep emissions cuts elsewhere. As our understanding of blue carbon systems grows, the message from current science is clear: the sequestration value of blue carbon is inseparable from the broader success of global decarbonisation. The warmer the planet becomes, the greater the weakness and unreliability of the blue carbon sink.

The viability of blue carbon as a mitigation option is therefore questionable and the use as offsets counterproductive. More broadly, it is becoming increasingly clear that humanity will need substantial Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) capacity to compensate for lack of past global mitigation and simultaneously respond to likely feedback from warming, whereby the earth system will take up an ever-smaller fraction of emitted CO2 over time. The limited CDR capacity available, as well as its uncertainty, means that CDR should not be counted on via offsets to counter-balance residual fossil fuel emissions that could have otherwise been eliminated.

Despite these uncertainties and cautions, policy momentum is outpacing awareness and readiness. Many countries have begun referencing blue carbon in NDCs, often qualitatively, without the robust measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) systems required for credible accounting. While the IPCC Wetlands Supplement provides methodological guidance, the actual implementation of these measures remains limited.

Blue carbon’s contribution to adaptation and resilience, however, is clearer and immediate. Healthy coastal ecosystems attenuate wave energy, buffer storm surges, stabilise shorelines, and sustain fisheries and local economies. Protecting them safeguards livelihoods and natural defences for millions of people in low-lying and island nations. Their benefits for water quality, biodiversity, and cultural heritage are tangible and enduring, even where mitigation gains are uncertain. Improving inventories, understanding Blue Carbon potential as adaptation option and improving governance, laboratory and technical capacity should be prioritised.

In climate finance, blue carbon now features in innovative instruments, including blue bonds, debt-for-nature swaps. It is also increasingly being discussed in relation to carbon markets. Despite this growing interest, these markets pose major integrity risks if pursued as substitutes for fossil fuel mitigation. Attempting to offset emissions through blue carbon credits would undermine 1.5°C pathways by delaying deep, cross-sectoral decarbonisation and exposing vulnerable states to reversal, double-counting, and equity risks.

Accordingly, the report outlines a recommended approach for responsible engagement:

- Protect and restore first: Prioritise avoided loss of existing ecosystems to ensure that the co-benefits of blue carbon ecosystems for mitigation and adaptation are retained.

- Build MRV capacity: Invest in science, data, and institutional systems to robustly monitor blue carbon ecosystem dynamics before seeking to establish baselines for the assessment of sequestration potential.

- Integrate cautiously: Reflect blue carbon in NDCs through qualitative, resilience-focused metrics, with a particular emphasis on adaptation-centred interventions.

- Exercise extreme caution toward carbon markets: Engaging in offsetting or trading mechanisms with blue carbon-based activities is not advised under current conditions. The inherent measurement uncertainty and impermanence of these approaches, taken together with growing climate impacts, risk undermining environmental integrity if connected to mitigation targets and impose liabilities upon reversal. Any future consideration of blue carbon quantification for accounting or financing purposes should be preceded by extensive regulatory, technical, and institutional preparatory groundwork, which will produce a long time series of inventories to support decision making as part of a robust MRV system. Environmental and social safeguards should also be sufficiently accounted for in any groundwork.

Instead of high-risk engagement with carbon markets, countries are encouraged to explore alternative innovative instruments of finance that favour results-based payments centered around ecosystem conservation and restoration, such as the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF). A blue carbon finance mechanism informed by the principles of the TFFF could prioritise the conservation and enhancement of ecosystem function rather than the monetisation of carbon. Payments would reward policy performance and verified environmental outcomes, providing countries with a predictable resource stream that strengthens national adaptation and coastal management systems without exposing them to the risks of offset markets.

However, direct replication of the TFFF model for blue carbon ecosystems is neither technically nor institutionally feasible. Further research and analysis is still needed to understand the articulate the instruments, costings, and potential returns of a financing facility for blue carbon ecosystem preservation. While unlikely to be directly transferrable to the context of blue carbon, the TFFF does illustrate the fact that climate finance can be mobilised at scale through non-market, policy-based mechanisms that reward ecosystem protection rather than the creation of carbon commodities. For countries seeking to strengthen resilience, support coastal communities, and safeguard ecosystems that are increasingly threatened by climate change, this offers a potentially compelling and lower-risk pathway that aligns with the priorities set out in this brief.

Blue carbon should currently be treated as a fragile, but vital asset with the potential to reinforce rather than replace the systemic decarbonisation required across all sectors. In this regard, blue carbon is not a silver bullet for countries seeking to meet mitigation targets, or generate climate finance, while avoiding emissions cuts in critical sectors across the national economy domestically and elsewhere.