New report finds ambitious action by G20 countries alone can limit warming to 1.7°C, keeping 1.5°C goal within reach

Share

New research by World Resources Institute and Climate Analytics shows the pivotal role that G20 countries must play to keep the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C within reach.

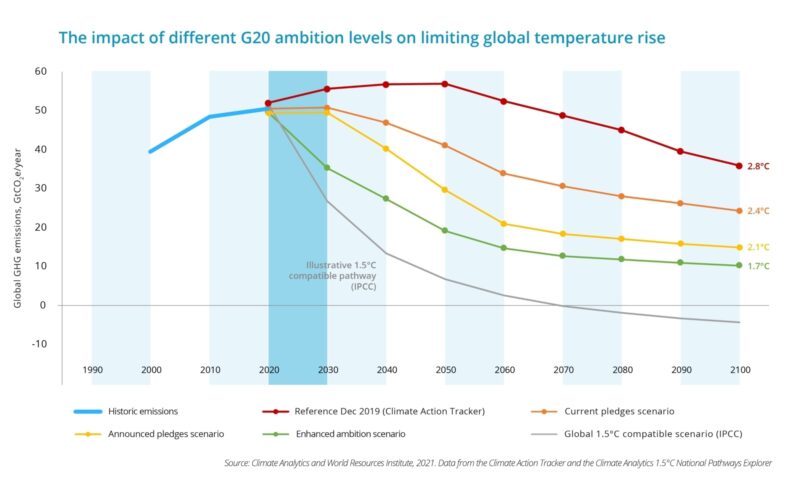

The report, Closing the gap: The impact of G20 climate commitments on limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C, finds that if G20 countries, accounting for 75% of global GHG emissions, set ambitious, 1.5°C-aligned emission reduction targets for 2030 and reach net-zero emissions by 2050, global temperature rise at the end of the century could be limited to 1.7°C.

Drawing on data and analysis from Climate Action Tracker and National Pathways Explorer, this report shows that current nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and legally binding net-zero targets put the world on a trajectory to 2.4°C of warming by the end of the century. However, some improvements by G20 countries are already in the pipeline: if G20 countries fully enact additional targets that have been announced but not yet adopted, temperature rise could be limited to 2.1°C. This represents substantial progress but is still far from sufficient to meet the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C temperature goal.

To assess how this gap could be narrowed further, this report modeled the temperature impact if all G20 nations align their 2030 emission reduction targets with a 1.5°C trajectory and achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, with a faster timeline for developed countries than for developing countries. The report finds that these ambitious actions by major economies alone could lower global temperature rise from 2.4°C to 1.7°C. This shows that 1.5°C aligned NDCs and net-zero targets from G20 countries could get the world three-quarters of the way to limiting warming to 1.5°C.

To ultimately achieve the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal, ambitious action in non-G20 countries is needed as well, along with greater efforts to rein in emissions from international aviation and shipping. Mobilizing developing countries to take ambitious action will require developed nations to substantially ramp up financial support to fund policies and projects to curb emissions and build resilience to climate impacts.

“The G20 is responsible for the vast majority of global emissions, and it’s clear from this report that we need the combined action of the world’s richest nations to limit warming to 1.5°C,” said Bill Hare, CEO, Climate Analytics. “Ahead of the Glasgow Climate Summit, the G20 governments must commit to taking much stronger action – to halve global emissions by 2030 – and developed countries must put money on the table for climate finance.”

To date, Argentina, Canada, the European Union, United Kingdom and United States are the G20 countries that have strengthened their 2030 emission reduction targets compared to the NDCs they submitted five years ago (learn more about these commitments and others via Climate Watch’s NDC Enhancement Tracker). Japan, South Africa and South Korea announced plans to strengthen their targets later this year.

China, India, Saudi Arabia and Turkey (responsible for 33% of global greenhouse gases) have yet to submit their updated NDCs. Meanwhile, Australia and Indonesia submitted updated NDCs with GHG emissions reduction targets identical to the submissions put forward in 2015. Even worse, Brazil and Mexico submitted plans that would allow higher emissions compared to their previous targets. Russia submitted a target that would allow higher emissions than its current “business-as-usual” trajectory.

“Action or inaction by G20 countries will largely determine whether we can avoid the most dangerous and costly impacts of climate change,” said Helen Mountford, Vice President, Climate & Economics, WRI. “That is why it is so egregious that Brazil and Mexico put forward weaker emissions targets than what they submitted five years ago, while China – the world’s largest emitter – has yet to commit to a 2030 emissions reduction target that aligns with its pledge to zero out emissions by 2060. To limit warming to 1.5°C, all G20 countries need to pull their weight and deliver ambitious climate plans ahead of COP26. And developed nations have a responsibility to fund climate action in developing countries.”

The report notes that many of the announced net-zero pledges by G20 countries need to be complemented by updated 2030 targets to align with their net-zero goals. If the 2030 targets are not strengthened, countries would need to follow steep emissions reduction trajectories after 2030 that would be out of step with feasible pathways to achieve their net-zero targets in a cost-effective way. These countries must rapidly curb emissions in the 2020s to get on credible pathways to achieve net-zero emissions by around mid-century.

The analysis presented in this report shows that, while all governments need to step up their climate commitments to reduce global emissions fast enough to be on a 1.5°C compatible pathway, G20 countries play a critical role in avoiding that temperature threshold. At the same time, developed nations have a responsibility to mobilize the trillions of dollars required to deliver climate action by developing countries. Delaying action would result in more costly and challenging rates of decarbonization in the years ahead and could push the 1.5°C goal out of reach.