Report: Hard-to-abate: justified - or an excuse for inaction?

This report looks at decarbonisation options for both the so-called "hard-to-abate" iron & steel - and cement - sectors, along with the lack of progress on CCS, and finds the claims they are hard-to-abate difficult to reconcile with reality.

Share

Claims from both the iron and steel - and cement - sectors that their emissions are "hard to abate" is slowing down real progress these sectors could be making on cutting emissions, according to a new report released today by Climate Analytics.

Instead, they are turning to a technological solution - carbon capture, utilisation and storage - or CCUS - that remains unproven, expensive, and does not reduce emissions to the levels needed to limit warming to 1.5˚C.

The report, " Hard-to-abate: a justification for delay?" analyses the latest scientific evidence about the opportunities to cut emissions from both sectors, as well as reviewing the current state of the CCUS industry in the context of these two sectors.

"Industry faith in the ongoing failure of CCUS is delaying urgent action to cut emissions - a new kind of greenwash based on technology that, frankly, doesn't work, and would not cut emissions from these sectors to zero," said report author and CEO of Climate Analytics, Bill Hare.

"The claim that iron and steel production as a whole is hard-to-abate is misleading. This mainly rests on the incumbency advantages of a particularly fossil fuel-intensive production route, for which there are technologically viable substitutes," the report says.

"While challenges of the technical and process-related emissions reduction in these sectors are non-trivial, the evidence presented in the report demonstrates that their decarbonisation is not only possible but highly achievable with existing and emerging technologies — especially when guided by integrated, whole-of-system approaches and supported by robust policy frameworks."

Iron and steel

The report finds that no more coal-fuelled blast furnace-basic oxygen furnaces (BF-BOF), which account for around 72% of steel production, should be built, and some existing plants must be decommissioned before the end of their economic life. This is particularly true in China, which has a relatively young fleet of the emissions-intensive blast furnaces.

It sets out available policy options for accelerating the retirement and replacement of hard-to-abate capacity and, with it, the overall perception of iron and steel as hard-to-abate. The solutions include demand reduction - including the increased use of recycled steel and improving material efficiency.

Achieving near zero steel will require substantial additional policy support, including ‘carrots’ such as investment in low emissions production, and ‘sticks’ of regulatory restrictions on high emissions production.

Cement

Addressing cement decarbonisation requires a comprehensive approach that moves beyond the conventional hard-to-abate view. While improving production efficiencies is crucial, it is equally or even more important to examine the entire lifecycle of cement, including the impact of demand management, end-use applications, and material substitution.

The report shows the world needs to reduce the overall use of cement to essential applications, but otherwise could be replaced with alternatives such as wood and stone. This, alone, could reduce cement demand by 20-30%.

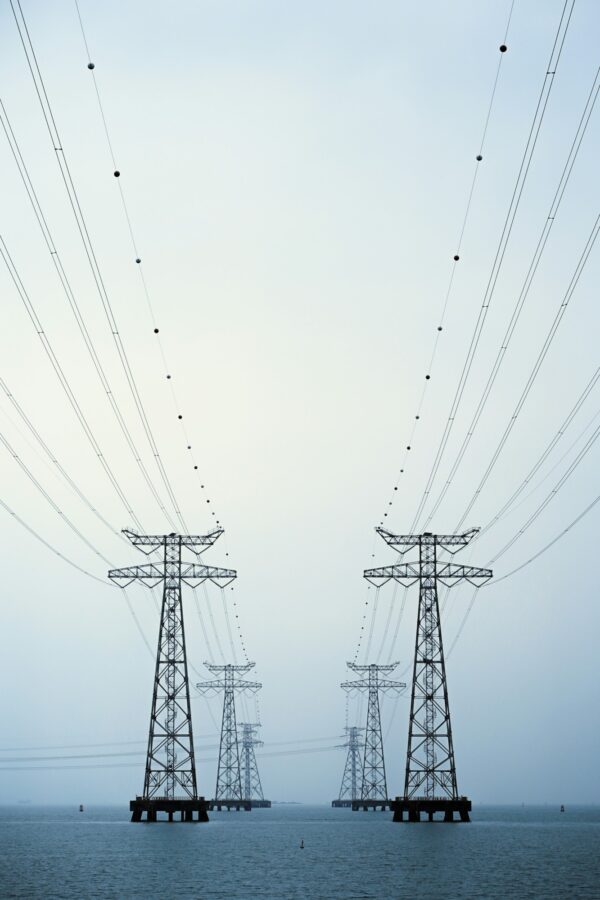

CCS/CCUS

The report also assessed the latest state of play on Carbon Capture and Storage, concluding from the published literature that it is not available at the scale and reliability these hard to abate sectors are claiming.

"Waiting for breakthroughs that may never arrive can disincentivise short-term investment and investigation of nascent technologies," said Hare.

The International Energy Agency has consistently cut its outlook for CCS: it has cut its outlook for CCS in the steel industry in 2030 by 61% since 2021, and for 2050 by 40%.

While the IEA retained a similar projection for the CCS role in the cement industry in its latest NZE report, it revised down its near-term outlook for CO2 captured in 2030 by 32%.

"Diverting finite policy support to applications that can feasibly stop emissions being generated, rather than those that might prolong emissions generation, appears a far less risky strategy," concluded Hare.