What's on the table? Mitigating agricultural emissions while achieving food security: analysis

Authors

Claire Fyson, Jasmin Cantzler, Ursula Fuentes, Matt Beer, Sebastian Sterl, Sofia Gonzales-Zuñiga, Hanna Fekete, Yvonne Deng, Lindee Wong, Daan Peters

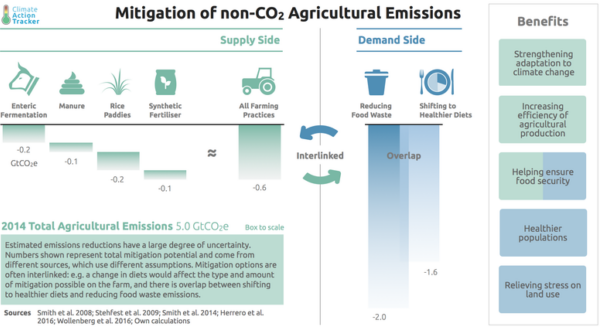

A new analysis of agricultural emissions by the Climate Action Tracker shows that reducing emissions through changes in farming practices alone will not be enough to limit global warming to 1.5°C, but changing our diets and reducing food waste could make significant additional reductions, which calls for a much more holistic approach. Agriculture accounts for roughly 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and as much as 50% of non-CO2 emissions, at 5–6 GtCO2e/year.

To limit warming to 2°C, we need to reduce agricultural emissions by at least 1 GtCO2e/year—an 11%–18% reduction by 2030 (and larger reductions thereafter), compared with a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario. However, to meet the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C warming limit, that reduction would need to more than double to 2.7 GtCO2e/year.

The briefing, as part of the CAT’s decarbonisation series, looks at options for mitigating non-CO2emissions from agriculture from two angles: key areas “on the field,” and trends in consumer behaviour. It addresses three main areas of action:

- changing farming practices

- reducing food waste

- changing diets

“Changing farm practices could lead to a reduction of 0.6 GtCO2e/year, but when combined with changing diets away from beef and dairy and reducing food waste, we could achieve a reduction of around 3 GtCO2e/year, possibly enough to decarbonise the sector to a 1.5°C pathway,” said Niklas Höhne of NewClimate Institute.“

Further research needs to look at the interactions between these areas, to reduce the uncertainty in total reduction potential.”

The main sources of non-CO2 emissions—methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O)—in agriculture are enteric fermentation, manure, synthetic fertilisers, rice cultivation, crop residues, and cultivation of organic soils.

No one global fix will fit all farming. In the EU, US and China, a large share of emissions is due to synthetic fertiliser usage, whereas in South and East Asia, emissions from rice cultivation contribute large shares, so mitigation options will vary by region. Smallholder farmers own 84% of farms, covering an estimated 12% of global farm area, so local circumstances will need to be considered.

The briefing addresses agriculture’s largest contribution to greenhouse gas emissions—cows—which contribute over a third of non-CO2 emissions in Europe, the U.S. and India, and over half in Australia and Brazil.

The main mitigation options include improvements in farming practices and a strong reduction in demand, but options need to be tailored to regional circumstances. There are also large gains to be made in reducing over-application of synthetic fertilisers, which have seen a stronger increase in emissions than any other agricultural source. A fertiliser tax could lessen this rapid growth, while also reducing other environmental concerns.

Solutions for rice cultivation—the next biggest source of emissions, making up over a third of emissions in many Asian countries—include draining paddies between planting seasons.If warming is kept well below 2°C and below 1.5°C, adaptation in agriculture may be able to compensate for some climate impacts, and the faster global emissions are mitigated and such impacts are avoided, the lower the burden of such adaptation.