Safeguards and exit points for the World Bank as host of the Loss and Damage Fund

Olivia Serdeczny, Manjeet Dhakal, Daniel Lund and Sneha Pandey

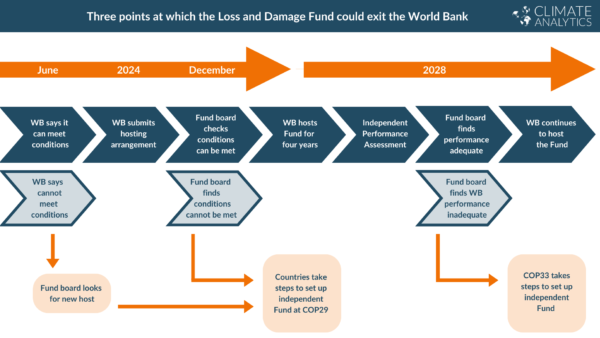

An agreement was reached to establish the World Bank as the interim host of the Loss and Damage Fund. Developing countries signed up to this on certain conditions. We unpack the safeguards put in place and look at the three points at which the Fund could exit the World Bank.

Share

A last-minute deal on the Loss and Damage Fund was finally struck at the fifth and final meeting of the Transitional Committee this month. The draft agreement – adopted at COP28 – establishes the World Bank as interim host. While a controversial choice, developing countries agreed to this on certain conditions.

We unpack the safeguards put in place and look at the three points at which the Fund could exit the World Bank.

Compromise: interim role for World Bank

There was a sigh of relief when the Transitional Committee finally reached an agreement after hurriedly scheduling an extra final meeting, yet the number of concessions settled on in the final moments to push through the ‘take it or leave it’ text curbed the enthusiasm in the room. The ‘agreed recommendations’ were also met with considerable push back from civil society observers.

Following the COP27 decision, developing country Committee members and the wider G77 have been united on the need to design a new, fit-for-purpose, standalone fund operated under the UNFCCC. Developing countries shared concerns around the working culture of the World Bank, its primary role as a lending institution, its donor driven and shareholder-based interests, and its rigid, inflexible policies.

To many developing countries, the World Bank’s profile flew in the face of key concepts and requirements for the Fund. For example, ensuring the fund can provide direct access to finance for vulnerable countries; the need for flexibility and responsiveness to different national circumstances; and the need for the Fund to receive financing from a wide range of traditional and non-traditional sources.

The World Bank’s ongoing struggles with reform and its perception as a soft power tool controlled by the interests of particular large donors exacerbated the narrative surrounding the Fund’s negotiations.

After facing an impasse at the fourth Committee meeting, developing countries demonstrated flexibility early on in the fifth meeting, coming forward with a compromise and willingness to entertain a potential interim hosting arrangement with the World Bank.

These concessions weren’t made lightly; developing countries worked to introduce a set of conditions and review periods to safeguard their concerns. If the recommendations and draft decision text are agreed at COP28, these safeguards will fundamentally define the final form of the Loss and Damage Fund.

Safeguards put forward by developing countries

Developing countries agreed a set of central conditions that the World Bank needs to adhere to over the initial interim period. Current World Bank policies would restrict the operations of the Fund and potentially override some of the key objectives of the COP27 decision that established the Fund. The conditions therefore seek to safeguard developing country interests and protect their role in the governance of the Fund.

The conditions imply that the rules and basic parameters outlined in the text would remain the basis on which the Fund operates. Otherwise, the World Bank might have designed the Fund according to its own approach. The conditions also state that the Fund’s Board, not the World Bank, selects the Executive Director. The Board can also set policies in relation to eligibility and access to the Fund, rather than relying on existing World Bank policies.

Importantly, the conditions specifically state that governments and non-traditional implementing entities (those beyond multilateral/regional development banks and UN agencies) can directly access the Fund. The overall gist of the conditions amounts to a package that ensures all countries oversee the design and operations of the Fund.

Three ways the Fund could exit the World Bank

If the World Bank meets all the conditions outlined in the Committee’s draft decision, it will become the permanent home for this historic new Fund, beyond the interim four-year period. The Fund under the World Bank would still be accountable to Parties to the Paris Agreement.

Meeting these conditions takes more than the World Bank saying they accept them. If it turns out that these conditions can’t or won’t be met during the interim period, countries have options to transition the fund to a standalone, independent entity within a host country, similar to the Green Climate Fund.

The final text includes three triggers that could cause the Loss and Damage Fund to exit the World Bank:

- The policy trigger: Within six months of COP28, the World Bank must communicate its willingness and ability to meet the stated conditions. If it is not in a position to proceed, the Board will launch a ‘selection process for a host country’ and begin work to establish a new standalone fund based on guidance agreed at COP29.

- The design trigger: Within eight months of COP28, the World Bank must submit an internally approved proposal on the Fund’s hosting arrangements to the Board. The Board then reviews this to determine if the overall design complies with the agreed hosting conditions. If the Board finds that under the World Bank's proposal conditions would not be met, countries can take steps at COP29 to set the Fund up as an independent entity. But, if the Board is satisfied, the Bank will be invited to host the Fund for an initial period of four years.

- The performance trigger: Towards the end of the interim four-year period (in 2028), an independent performance assessment of the hosting arrangement will take place. Based on this and its own considerations, the Board will decide whether or not the conditions have been met. If not, countries will take steps to establish a new standalone fund at COP33. If the Board is satisfied, the World Bank would continue to be the host of the Fund.

This carefully constructed process of reviews and checks and balances gave developing countries enough assurance to trial the World Bank option in good faith.

Compared to the ‘taboo’ status of loss and damage over the last three decades, the speed of recent progress, despite the range of challenges faced, is astonishing. But then the need is also urgent. Evidence of the links between human-induced climate change and escalating climate disasters, such as the ongoing agricultural drought in Syria, Iraq and Iran, is piling up.

In countries where people are losing their homes and lives, reconstruction efforts are swallowing up national budgets and causing growing debt stress. As climate impacts worsen and compound, the issue becomes more and more urgent. While the Transitional Committee has completed its task, the important work of setting up the fund and make sure it delivers is just beginning.