From volcanic eruptions to tropical cyclones - adaptation and disaster risk reduction are still a question of finance for small islands

Tessa Möller, Patrick Pringle, Tabea Lissner, Adelle Thomas

Share

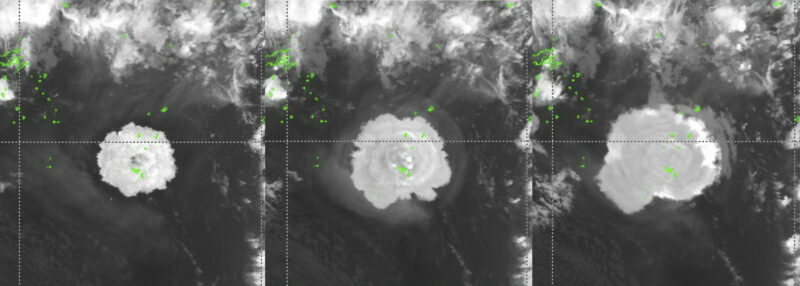

A dire example of this is the recent eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano in Tonga. Combined with the Covid-19 pandemic, the eruption is likely to further limit the country’s adaptive capacity.

The eruption caused a massive volcanic ash plume that covered all of the country’s roughly 170 islands and directly impacted more than 100 000 people. It triggered tsunami waves of several meters, with damages extending to Fiji, Vanuatu and as far as coastal parks along the US West Coast. Three people lost their lives.

The toxic ash contaminated water in rainwater tanks and the tsunami wave salinised the groundwater resources, with dire implications for water access. Freshwater has had to be flown in from New Zealand.

On top of all this, the country is now going into lockdown after recording Covid cases among international aid workers.

Trade-offs

The destruction caused by Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai comes on the heels of nearly two years of social isolation and economic disruption. SIDS such as Tonga have been amongst the most vulnerable, and most affected by the economic impacts of the coronavirus pandemic, due to the heavy reliance of their economies on tourism and fisheries.

Up until very recently, Tonga’s population had been insulated from Covid-19 due to its isolation, a silver lining considering the country’s modest intensive care infrastructure. It is a great irony that the arrival of aid for one disaster should potentially trigger another – but one that illustrates how deeply interwoven these vulnerabilities are.

How does this relate to climate change?

Freshwater contamination is a great example. Freshwater shortages and drought conditions are already regularly experienced in many SIDS due to climate change. Long before some atoll nations may be totally inundated from sea level rise, they will lose their groundwater resources to wave-driven flooding and salinisation.

To cope, communities rely on water-sharing, or purchasing water from private companies. In the worst cases, people may be forced to change their livelihoods or to relocate. In Caricou, Grenada, increased migration rates have been observed shortly after droughts.

Short and long-term risks to water security require effective adaptation solutions. But it’s never that easy.

As we have seen, natural disasters, such as volcanic eruptions or tropical cyclones, often leave affected communities more vulnerable, including to climate change impacts. Economic resources are then targeted towards short-term post-disaster needs, resulting in fewer resources available to address future impacts through implementing long-term adaptation projects.

Compounding debts

High levels of debt. are pronounced in many SIDS and servicing these debts requires ongoing payments, which further reduces national budgets available for sustainable development, disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation.

Today, impacts from climate change are already contributing to increasing debts in the Caribbean SIDS. In 2015, the Caribbean region’s total debt service payments represented on average over 20% of total government revenue. In the future, with projected increases in the intensity of extreme events, the debts are likely to grow.

Financial constraints have repeatedly been reported as the main factor hindering adaptation in SIDS. In 2009, rich countries pledged to channel US$100 billion a year for developing countries, but this goal has been substantially missed. Furthermore, the bulk of climate finance spent so far has focused on mitigation and only 20% has targeted adaptation.

Moreover, the Green Climate Fund has approved the least amount of funding for SIDS compared to other regions. Middle-to-high-income Caribbean SIDS are not eligible to access certain climate finance.

The solutions

To address some of the financial constraints, debt for climate swaps has been discussed as an alternative to climate finance in developing countries and recently in SIDS. Here, the debtor nation would make payments in the local currency to finance adaptation projects, and as exchange, multilateral or bilateral debt would be forgiven by creditors.

Similarly, in the case of the Tonga volcano eruption, debt swaps could also be an alternative for financing post-disaster reconstruction.

Strengthening synergies between climate adaptation and disaster risk reduction is also essential. In SIDS, they often require similar measures – so with the right finance, resources and effective governance policies integrated solutions can be found for both.

At the regional level, the Pacific has brought together climate adaptation and disaster risk reduction into a single regional framework and is increasingly being seen in joined-up approaches at national level. For example, Tuvalu has formulated a Sustainable and Integrated Water Sanitation Policy linking both disaster risk reduction and adaptation to each other, but is making only modest progress on its implementation due to finance and capacity constraints.

Under the Glasgow Climate Pact, the need for scaling up and rebalancing adaptation finance is well emphasised. This year’s COP27 in Egypt could create new momentum for mobilising and scaling up finance for developing countries, to not only tackle mitigation and adaptation, but also loss and damage.

It’s vital that efforts to rebalance global adaptation finance give specific consideration to dealing with compound and interacting risks, especially in the most disaster-prone areas of the world.

Image: Eruption of Hunga Tonga–Hunga Haʻapai Volcano captured by the Meteorological Satellite Center of the Japan Meteorological Agency (CC BY 4.0 DEED)