Centred on science – how the IPCC can guide mitigation action

Michiel Schaeffer, Ursula Fuentes Hutfilter, Robert Brecha, Claire Fyson, Bill Hare

Share

The IPCC Special Report on 1.5°C contains the best available science to guide the development of Long-Term Low greenhouse gas Emission Development Strategies (LT-LEDS), which are due to be submitted in 2020 under the Paris Agreement. One of the essential functions of LT-LEDS is to provide a long-term 1.5°C consistent trajectory as an essential guide for increasing the level of mitigation ambition in the updating of NDCs, also due in 2020. LT-LEDS can provide essential guidance for short-term (5, 10 year) emission mitigation outcomes and targets, particularly as under the Paris agreement and NDCs are to be updated every five years.

Coupling the development of LT-LEDS with the process of updating of NDCs is very important to avoid inconsistencies between short-term goals and longer term required outcomes. LT-LEDS are an opportunity to integrate across different timescales the policies needed for systemic and transformational change in all economic sectors with sustainable development goals. However, enhancing current NDCs is urgent now, even if a 1.5°C-compatible LT-LEDS is not yet available during that process, and thus may need to be based on preliminary guidance on 1.5°C compatibility. Coupling the process of developing full LT-LEDS and submitting these by 2020 will make the process of further ramping up NDCs more coherent in the years to come.

Climate Analytics report: “Insights from the IPCC Special Report on 1.5°C for preparation of long-term strategies”

The urgency of dealing with climate change is clear. It is clear to communities around the world experiencing ever more severe impacts, like extreme weather events that can be linked to climate change with an ever-greater certainty. It is increasingly clear to investors, who have started backing away from fossil fuels. What is also clear is that although governments have committed to pursue efforts to limiting warming to 1.5°C by ratifying the Paris Agreement, the emission reductions resulting from the commitments – termed NDCs – countries have put forward are vastly insufficient to achieve that goal and will lead to 3oC warming by 2100. NDCs must be upgraded before the end of 2020.

One of the key findings of the IPCC SR1.5 is that achieving the Paris Agreement goals may not be possible, unless 2030 emissions are reduced substantially below where they are headed under the present NDCs.

As a consequence, to ensure that Paris Agreement long-term temperature goal can be achieved, upgrading of NDCs by 2020 needs to be guided by a long-term trajectory consistent with 1.5°C. This would be an essential function of what the Agreement refers to as “Long-Term Low greenhouse gas Emission Development Strategies” (LT-LEDS). LT LEDS will also provide guidance for the next five-yearly update of the Paris agreement NDCs due by 2025, following the Global Stocktake in 2023/24.

The Paris Agreement states that emissions reductions should be guided by the “best available science” and this is exactly what the IPCC Special Report on 1.5°C provides to guide governments in developing these long-term strategies.

Global emission reductions and sector transformations for 1.5°C are clear

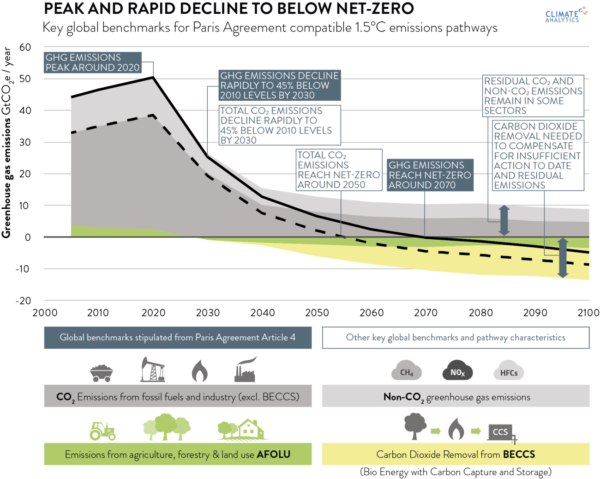

In a typical global 1.5°C pathway CO2 emissions peak in 2020, decline by 45% from 2010 by 2030, get to zero by 2050 after which they go negative through removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere using a range of natural and technological options.

The sectoral changes to accomplish these global reductions boil down to a few essentials that apply to climate policy worldwide:

- Electricity – end coal use in the power sector before 2050 globally. Renewable energy reaches a share of over three-quarters by 2050. Natural gas, replacing more carbon-intensive coal, can play a transitional role in decarbonising electricity generation. Its continued use would only be consistent with the Paris Agreement temperature goal if it is used with carbon capture and storage (CCS), which is increasingly unlikely to be able to compete with renewable energy due to incomplete capture rates, no observed cost improvements and more limited co-benefits. As a result, very little gas (8%) remains in the fuel mix by 2050.

- Transport – electrification of rail travel (passenger and freight), heavy-duty vehicles (HDV) for freight transport, but most especially, for light-duty vehicles (LDV) is key in transport, in parallel with modal shifts (e.g. increases in passenger-trips by public transportation, shifts from trucks to rail, more bicycles and walking as part of urban planning). Electrification of LDVs represents a dramatic increase in efficiency, decrease in emissions, and decrease in operating and maintenance costs for consumers.

• Industry – changing processes through electrification, or use of hydrogen (e.g. direct reduction of iron ore with hydrogen for steel production, or heat generation with electricity) and sustainable bio-based feedstocks for non-electric energy demands or for chemical feedstocks. For some processes, the use of Carbon Capture, (Utilisation) and Storage (CC(U)S) is part of this strategy, in particular where process-related emissions cannot be avoided, such as cement production, but progress has been very slow thus far. Another important strategy is substituting carbon intensive products with other products (e.g. replacing steel or cement with wood or plastic with textile fibres). - Buildings – electrification of and higher efficiency in thermal conditioning (e.g. heat pumps with an increase in efficiency of a factor of two to three compared to typical present-day systems).

- Sector coupling – with far-reaching electrification of sectors, sector coupling becomes essential with a fully decarbonised electricity sector.

- Agriculture – enhanced agricultural management (e.g. rice paddy water management, manure management, improved livestock feeding practices, and more efficient fertiliser use), as well as demand side measures such as dietary shifts to healthier, more sustainable, low-meat diets and measures to reduce food waste

- Rest of land sector – steep reduction in deforestation and the adoption of policies to conserve and restore land carbon stocks and protect natural ecosystems. By 2050, net CO2 uptake in this sector will already need to be on a multi-Gigatonne scale

A major shift in investment patterns is needed to enable these necessary sectoral transformations. In the next 20 years investment in low-carbon energy technologies and energy efficiency will need to double while investment in fossil fuels should decrease. This would mean that global annual investments in low-carbon energy technologies overtake fossil investments already by around 2025.

If financial flows are redirected towards underinvested assets, such as infrastructure and buildings in a timely manner, the necessary transformation in these sectors can be achieved without creating stranded assets.

Translate global pathways to guide national and sub-national action

These are the IPCC’s finding at the global sectoral level, though. To help guide governments in defining their own 1.5°C compatible short- and mid-term targets, these global pathways need to be translated into sectoral guidance and benchmarks at national and sub-national scale.

We have done this, for example to derive a coal phase out timeline for the EU, Germany and Japan. As part of the Climate Action Tracker, we have also looked at what’s needed to scale up climate action in the EU across several sectors. In another study, we assessed whether Western Australia’s gas extraction plans are in line with the Paris Agreement. We’ve also been able to show what emission reductions are necessary for Finland and the EU to be in line with the 1.5°C limit, both according to energy-economics and according to what is “fair” in terms of factors like historical responsibility for climate change.

This Climate Analytics work – and our ongoing and future work providing national 1.5°C pathways – will help to guide priorities of governments and enable them to take advantage of coupling between sectors to reduce costs and avoid locking in carbon intensive infrastructure and practices.

Opportunities for long-term national strategies and enhancing near-term action

With global pathways translated into guidance at national level, what should a LT-LEDS process take into account and accomplish? Besides analysing sector transformation, the Special Report on 1.5°C provides assessments of synergies between climate-change mitigation and adaptation with other policy areas, and in particular an innovative mapping of synergies and trade-offs with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Where there are trade-offs, the IPCC shows that these can be managed or overcome with appropriate design of policies. Perhaps the most critical message from the IPCC SR1.5 is that achieving the 1.5°C limit is made much easier through the pursuit of sustainable development policies, and vice versa that achievement of many of the sustainable development goals is critically dependent on limiting warming to 1.5°C. As a consequence it is clear that LT-LEDS strategies should not be limited to a single sector, but follow a whole- economy approach, considering opportunities and challenges in each one, and reduce demand and improve efficiency across all sectors.

The process of developing and implementing LT-LEDS then should engage government departments across sectors and levels, and enhance institutional strength, and, crucially, be coupled with the process of updating NDCs by 2020. It is important that the strategy process also engages non-government actors/stakeholders to enable societal transformation. It seems clear that such a broad approach is needed to achieve far-reaching aims like the accelerated uptake of renewable energy and storage technologies, and electrification of end-use sectors (transport, building, industry). Broad engagement is also required to mobilise resources and capacities to ensure timely shifting of investments at scale.

In the process of LT-LEDS development and in considering enhancement of NDCs, both due in 2020, learning should be strengthened continuously by implementing monitoring and evaluation processes, and engaging scientific institutions. Developing countries should identify the needs for financial, technological and other forms of support to build capacity to mobilise resources and the international community should assist achieving this.

Developing a LT-LEDS coupled with NDC enhancement is an opportunity to address the systemic and transformational change in all economic sectors and integrate these with sustainable development. Synergies with sustainable development goals provide many more opportunities in relation to food security and public health, access to clean and affordable energy, alleviation of poverty, and reducing impacts on biodiversity. Addressing and enhancing synergies with adaptation is another major opportunity.

Governments should and can build on and accelerate the ongoing transformations, such as the uptake of renewable energy and social innovations towards zero carbon solutions for energy, and urban and transport infrastructure.