Responding to a global crisis - the coronavirus pandemic and the climate emergency

Carl-Friedrich Schleussner, Matthew Gidden, Kim Coetzee

Governments around the world are doubling down on containing the COVID-19 pandemic, showing what a response to a global crisis – also the climate crisis - can and should look like: government action informed by science, individual behavioural change enabling the transformation, and leaving no one behind while focusing on protecting the most vulnerable.

(This article is also available in German)

Share

This article is also available in German

The coronavirus pandemic and climate action in 2020

The impact of the coronavirus pandemic on economic activity has reduced greenhouse gas emissions. However, the narrative that this is “good” for the climate is dangerously misleading. Rapid decarbonisation requires strong economic systems, including capital, as well as research and development investment. A global recession might slow this transition. Also, secondary effects may have far-reaching implications: for example, a substantial drop in demand for fossil fuels will likely make them cheaper, potentially slowing the move to climate-friendly, but currently more expensive, alternatives like electric vehicles.

2020 is a decisive year for global climate action. Under the Paris Agreement, governments are required to put forward stronger emission reduction pledges (National Determined Contributions, or NDCs). According to the Climate Target Update Tracker, only four countries have done so to date. The IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C states that it found with “high confidence” that if emission reduction efforts over the next decade are not significantly scaled up, the 1.5°C limit of the Paris Agreement will be out of reach. Governments though are now fully focused on the pandemic (and rightly so), including addressing the resulting economic effects, and popular movements are taking good-practice measures to reduce in-person events (e.g., the Fridays for Future movement has cancelled demonstrations), making it increasingly difficult to create political momentum towards updating of the NDCs, however urgent this may be.

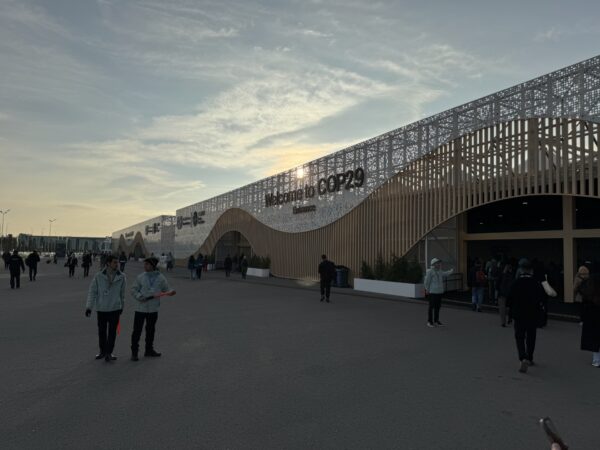

International climate negotiations that require diplomats and experts from all over the world to participate are also affected by the pandemic. The UNFCCC has announced it will hold no physical meetings until the end of April. Even the annual June meeting, the last UNFCCC negotiation session ahead of this year’s climate summit in Glasgow (COP26), could be at risk. It is impossible to foresee how the pandemic will evolve but cancelling the summit is even a distinct possibility. To make matters worse, Italy, which is meant to run some key preparatory meetings ahead of COP26, has introduced country-wide restrictions.

Considerations of COVID-19’s effect on the climate need to go beyond short-term emission reductions – and the political and economic outlook is all but rosy. Reasoning that an economic downturn and crisis can tackle climate change is not only mistaken; it could undermine public support for climate action. Tackling the climate crisis is about decoupling wealth and growth from emissions and ensuring a sustainable future for all, not economic decline.

Coronavirus responses – a blueprint for individual and government action in a crisis situation?

The importance of individual vs. government actions to address a collective crisis is a hot topic in the climate debate.

While individual actions, like improving hygiene, limiting travel and avoiding public events, can help reduce the spread of the virus, these alone are insufficient. It is up to governments to address this collective problem. For one, the virus affects some vulnerable groups more than others, so there is a collective responsibility to protect them. Secondly, people need clear guidance, if individual action is to be coherent.

The 2018 IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C suggested that changes in human behaviour and lifestyles are necessary and are “enabling conditions … for 1.5°C-consistent systems transitions.” Altering dietary habits or adopting more sustainable consumption and mobility patterns can reduce our individual climate footprint. In the context of a recognised emergency, such changes can be perceived as common sense measures, just like washing one’s hands.

In addition to drastic actions, like locking down whole cities, provinces or states or suspending international travel, many governments are also implementing measures that relate to guiding individual behaviours – like encouraging those who can to work from home, cancelling public events, and suspending schooling. Most government responses to the pandemic heed the recommendations of experts, such as the World Health Organization. Unfortunately, as with climate, this is not the case for all, and we do not argue that the response by governments around the world has been adequate. Our argument here focusses solely on the central role governments must play in responding to the corona pandemic, as well as the climate crisis.

Government action can also help to tackle a problem that is all too familiar to those in the climate sphere: the problem of “free-riding”. Even if most members of society (or countries) drastically change their behaviour – potentially with considerable individual sacrifice – the free-riders who do nothing but benefit from the actions taken by others may undermine the collective effort.

Crucially, only governments are in a position to provide support to those most affected by the measures taken to contain the pandemic – for example the transport and tourism sector, and to address the risk of a global recession. Taking measures to maximise the crisis response is essential for reducing its potentially disruptive nature.

In tackling the climate crisis, even the most stringent responses would be much less abrupt. Urgently needed actions include pricing carbon, divesting and removing fossil fuel subsidies, and phasing out coal. However, ensuring a just transition is an important element of any government policy, for example the proposed European green deal

Just as with the corona pandemic, suggesting that individual action alone can “save the planet” is misguided. Achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement requires robust action from governments to set the societal boundaries to address the crisis collectively, informed by the best available science.

A chance for change?

Some of the responses to the coronavirus have had immediate, unintended climate benefits. For instance, the substitution of in-person meetings with teleconferences has led to cancelled flights and reduced aviation emissions. Even the IPCC recently announced that its next lead author meeting would be held virtually: several hundred scientists from all over the world will connect through video conferencing. Could these changes herald the emergence of a lower energy demand future for global communications and travel?

Countries will need economic boosts during and after the crisis to recover. As in the case of climate cooperation, international solidarity is urgently needed for an inclusive recovery, as poor or especially heavily affected countries will lack the resources to do so. Such investments and programmes, while obviously focusing on addressing the near-term shock, present a long-term opportunity also for the climate. Whether these stimuli will be based on fossil fuels or future-oriented and climate-friendly alternatives will determine whether this health crisis can be a turning point in the global response to climate change. There are opportunities to respond to this public health emergency in a way that it leverages efforts towards a much needed acceleration of action to address the climate crisis.

This blog was written as part of the project “NDC 1.5°C Pathways” funded by the IKEA Foundation.