Update: the dangers of blue carbon offsets: from hot air to hot water?

Share

As the interest in using nature-based solutions to mitigate climate change grows, ‘blue carbon,’ which means carbon sequestered in coastal ecosystems, is also garnering attention. A number of countries have proposed including blue carbon in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), and there is growing interest among some governments and fossil fuel companies in blue carbon as an offset mechanism.

This briefing unpacks the key challenges and risks associated with the blue carbon concept by considering three key questions. What is the real potential of blue carbon as a mitigation measure? To what extent is carbon storage in coastal ecosystems threatened by current and future climate impacts? And is there a danger that focus on blue carbon could detract from reducing emissions from fossil fuel use?

Blue carbon refers to the carbon sequestered in coastal ecosystems – namely mangroves, sea grasses and salt marshes.

Key messages

Using blue carbon to achieve national mitigation targets risks diluting mitigation ambition in other sectors, which could jeopardise our ability to limit warming to 1.5°C. Blue carbon must not be a replacement for rapid emissions reductions in other sectors.

The climate effects of carbon stored in natural ecosystems and carbon emissions from fossil fuels are not equivalent. This means any attempts to measure and set targets for carbon sequestration in coastal ecosystems should be kept separate from emissions targets in other sectors. Lessons from accounting for carbon flows in land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) have shown that integrating nature-based mitigation offsets under national mitigation targets creates loopholes, hot air, and measurement, reporting and verification (MRV) challenges.

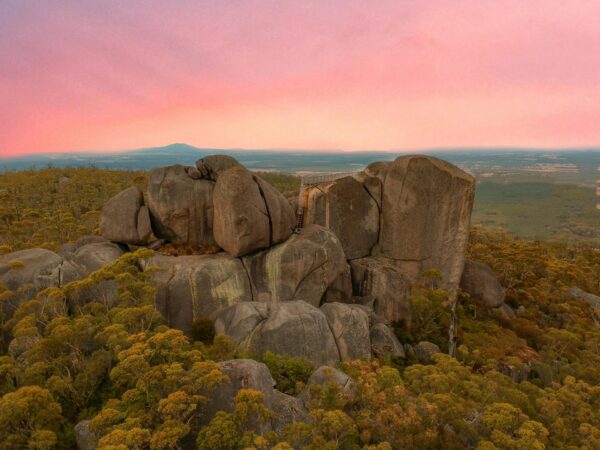

Under present reporting and accounting arrangements losses from extreme events and climatic disturbances do not have to be counted by governments as emissions. For blue carbon, this would mean that the losses of carbon from marine heatwaves, sea level rise extreme events or multiple stressors would not be recorded in national emissions accounts, even though the prior storage of carbon could have been counted as a sink towards climate targets. Recent die-back of coastal ecosystems during heatwaves (e.g. in Shark Bay, Australia) have illustrated how significant the losses of carbon can be.

Focusing on the climate sequestration component of coastal ecosystems within a mitigation context is also problematic because their potential to reduce emissions and draw down CO2 from the atmosphere is highly uncertain and too small to be an effective mitigation strategy. The IPCC found that coastal ‘blue carbon’ ecosystems have a limited global sequestration potential of about 0.5% of present day emissions annually (SROCC, IPCC 2019).

Ecosystem restoration may only provide benefits if global emissions remain low. The vulnerability of coastal ecosystems to climate change impacts means that the effectiveness with which they draw down carbon and the permanence of their carbon storage may be jeopardised under the levels of warming and sea level rise implied by the current set of emission reduction commitments (Nationally Determined Contributions or NDCs).

According to the IPCC, exceeding 1.5°C would lead to the near-complete loss of tropical corals, and warming of 3°C or more – where current NDCs are taking us – would lead to high to very high risks for many coastal ecosystems (including seagrass, salt marshes and kelp forests) (SROCC IPCC 2019).

It is essential to prevent the degradation of coastal ecosystems, but carbon sequestration is not necessarily the most valuable service these ecosystems provide. The wealth of potential co-benefits from coastal ecosystem conservation and restoration, beyond carbon sequestration, are justification enough for schemes to incentivise their protection. Additionally, there are substantial capacity constraints for the measurement of ecosystem-related carbon fluxes in many developing countries.

In summary, the science is very clear: protecting coastal ecosystems and the valuable services they provide – including in adaptation – requires rapid emissions reductions in all sectors to limit warming to 1.5°C. High uncertainties and impermanence pose significant risks to the use of blue carbon removals as an offset for other emissions (e.g. natural gas emissions) remaining high, or their transfer in the Paris Agreement’s market mechanisms. Treating nature-based mitigation as equivalent to any other form of mitigation could have dangerous consequences for the ecosystems that such measures would seek to protect.