Making use of latest science in adaptation planning

Delphine Deryng, Adelle Thomas, Kouassigan Tovivo

Share

Scientific evidence points to the fact that climate change impacts will be more dramatic in certain regions. Many of the world’s poorest countries are in those regions and are most vulnerable to climate change impacts – the Least Developed Countries and Small Island Developing States. They have very limited capacities and resources, and relevant scientific information is sparse or difficult to access, yet effective climate change adaptation planning requires that science and policy come together.

At a session we organised at the Adaptation Future conference in Cape Town, a diverse group of participants, including researchers, adaptation practitioners and policy-makers, gathered to brainstorm how to overcome barriers commonly experienced while working in the field of science-based climate adaptation in developing countries. In two of our projects, PAS-PNA and IMPACT, we focus on solutions for enhancing the development of science-based adaptation strategies in West African LDCs and SIDS. In this session, we wanted to discuss difficulties and strategies in dealing with them with other experts.

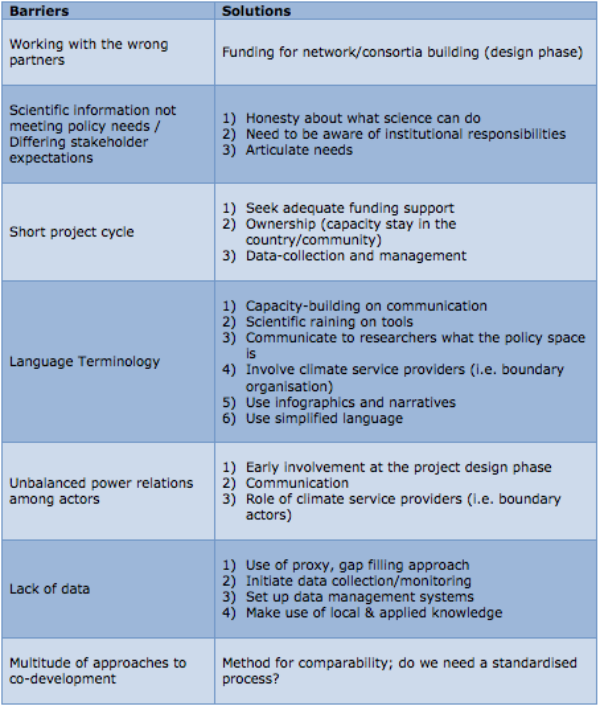

Overcoming barriers to science-policy communication

Scientific information tends to be packaged and transmitted in complex language, terminology and concepts that do not reflect in practical terms their policy relevance or priority. Ensuring a two-way communication process is crucial because top-down knowledge transfer that starts with generating scientific information first and then communicating it to policy-makers has proved ineffective. However, unequal power relations between researchers and policy-makers as well as disciplinary barriers undermine effective, regular and durable communication between these two groups of stakeholders.

Workshop participants in this group came up with a couple strategies that can be used to address those challenges:

- Research funders should put forward requirement and sufficient funding for early stakeholder engagement to co-identify the research questions; this will convene policy-makers and end-users to clarify priority and needs, and increase awareness of institutional responsibilities among all groups holding a stake in the project.

- Communication training for both knowledge producers and users will improve researchers’ understanding of the decision space and help ensure science is conveyed in an understandable language to policy-makers. Making use of infographics and participatory narratives, for example, was mentioned as an effective way to improve science-policy communication.

Towards Knowledge co-production

Building a two-way knowledge transfer process between science and the policy sphere (knowledge co-production) is an essential step for anyone working in the field of climate adaption, but it poses many difficulties.

One central factor in successful knowledge co-production is trust and equal engagement among all stakeholders of a project. There was a strong consensus among the participants that trust building requires time and needs to be planned ahead to ensure enough time and resources is allocated to this key step of the work. Co-development is needed from the project design phase. Methods such as participatory scenario development and hands-on interaction with scientific tools can greatly enhance the involvement of stakeholders and their access to science products to non-scientists.

Communication has a key role to play in ensuring equal power relationship among individual stakeholders. There’s not one single approach to co-production but it can be useful to compare different approaches; learning from past mistakes and challenges can sometimes offer unique insights to solutions.

Adaptation planning in a data-poor environment

What to do when there is no data, yet adaptation planning still needs to happen? The lack of robust scientific records on climate information is a recurring issue in least developed countries and small island developing states. Participants in this group identified two golden rules for adaptation planning in data-poor environment.

- Focus on what is available and not what is optimal or ideal. There’s also a rich but under-exploited pool of information emerging from non-academic work. A creative approach to what type of information can serve as proxy, such as church records of floods, can be another way to collect information and fill gaps in time-series.

- Encourage the development of a data collection program and initiative, by creating incentives for people in communities to collect and monitor information themselves and engage in the data collection process. Such direct involvement can further stimulate a sense of ownership and benefit the co-production process highlighted above.

In-country scientific awareness and capacity building

In developing countries, the production, awareness and usage of regionally or nationally relevant scientific information for adaptation planning is often limited, which adds challenges to science-based adaptation. Unequal power relationships between developed countries, where the generation of scientific information is often concentrated, and developing countries, where robust scientific information is needed, can create challenges for science-based adaptation planning.

There are several approaches to address these challenges:

- Local knowledge can be used to collect needed data, to identify local challenges and to highlight gaps in policy-relevant scientific information. The inclusion of local knowledge in the production of scientific information increases relevance and ownership of outputs.

- Regular exchanges between producers of scientific information and end users must be convened. These meetings build trust, increase capacity to utilise information and ensure the relevance of information.

- Capacity building must move beyond the initial receivers of any training and be institutionally mainstreamed. This can take the form of “train the trainers” approaches, so that capacities of more people can be improved. Last, increasing access to scientific information is critical to improving awareness and usage. This can be achieved through making regionally relevant scientific studies easily available and by increasing awareness of and connections to regional researchers.