Germany's coal exit law, or the politics of inertia

Share

This year, global coal demand is set to experience its largest fall since World War II, setting off a spate of canceled coal plant capacity expansion plans across the world. Almost paradoxically it seems, Germany has allowed a new coal power plant to start operating – unfortunately this is not the end of the story.

While it is positive that Germany is moving to legislate the phasing out of coal, the draft law threatens to undermine Germany’s place in history as a climate policy leader as it would allow highly polluting lignite to burn well into 2038 – long after 2030 when coal fired power plants in the OECD need to be phased out to meet Paris Agreement goals.

The draft law is based on the recommendations of the coal commission, which were incompatible with the goals of the Paris Agreement to begin with. But even members of the coal commission have criticised the law for not even being in line with their – already too weak – recommendations.

The draft law currently includes provisions to phase out coal by 2038, and includes three reviews after 2026 to evaluate whether this date can be brought forward to 2035. It ignores the science-based phase-out dates, adopted by international coalitions such as the Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA), that require OECD countries to phase-out coal from the power sector by 2030. Even if based on the first round of review in 2026 it is decided that coal phase-out needs to be accelerated, the law would allow for the coal exit date to be brought forward by three years.

Germany’s entry into the PPCA last year should have been a clear signal for it to move the discussed phase-out date forward from 2038 to 2030, especially as Germany’s joining was accompanied by a statement highlighting how “it sends a clear message to other parts of the world”.

While emissions from coal power generation have been dropping in 2019 – pre-COVID – and more in the first quarter of 2020, Germany missed the opportunity to start the coal phase-out in 2020.

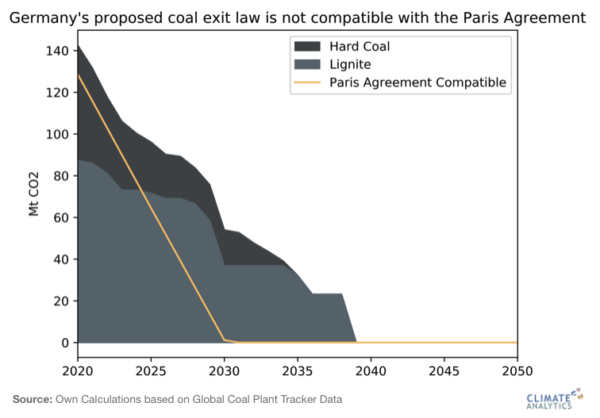

The figure above shows the emission pathway (1) implied by the law compared with a Paris Agreement compatible pathway, which we modelled in a report in 2018. The cumulative emissions that the draft law will likely lock in amounts to nearly 1.3 GtCO2 until 2038, or about 16% of Germany’s entire Paris Agreement compatible carbon budget to 2050 (2). We estimate that this is nearly twice as much as Germany can emit from coal power generation if it aims to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.

A key reason for these significant locked-in emissions was the decision to effect retirements, especially of lignite plants, close to the defined years in the schedule, rather than opting for a linear reduction proposed by the coal commission. If this retirement schedule is adopted in law the operators of lignite mines and power plants can laugh all the way to the bank, secure in the knowledge that they may be able to sue the government for ‘breach of contract,’ should they be required to retire their ‘cash cows’ earlier. By overusing the carbon budget, the coal power sector will place more pressure on other sectors to reduce faster and in a more costly way than would otherwise be necessary.

It is important to note that the value of these coal mine and power station assets was already plummeting with coal losing competitiveness as it comes under pressure from both rapidly declining costs of renewables and higher prices of emissions allowances in the framework of the reformed EU Emissions Trading Scheme.

Despite this decrease in the value of the assets, the coal exit law provides a cushy retirement and large transfers of financial resources to incumbent power generators. This reflects a ‘politics of inertia’ that increasingly appears to drive German policymaking in the field of climate and energy policy and that ignores scientific analysis, as well as the needs and demands of an increasingly vocal, citizen-driven climate movement.

But what about the people in the affected regions? The government argues that a delayed lignite phase-out (ignoring the issue of transfers to mining companies and power utilities) was necessary to allow time for structural change and support for the mining regions. However, researchers have shown that a more rapid lignite exit, while leading to higher short-term structural impacts, would be accompanied by a quicker recovery. A more rapid coal phase-out would also be accompanied by several co-benefits including reduced environmental pollution and associated health impacts.

This is certainly not the vision of an Energiewende, or energy transition, that Germany seeks to export to other countries.

We have shown previously that the mandate for the coal commission had a fundamental flaw: it ignored the need for Germany to increase its own emission reduction targets for 2030 in order for the EU to significantly increase its inadequate NDC target from the present 40% domestic reduction. This is a concerning signal to other EU countries that are currently dragging their feet on increasing their targets. Germany will hold the EU presidency for the second half of 2020 and has a stated aim to facilitate the adoption of a more stringent emission reduction target for the EU as whole.

Germany has shown leadership recently by supporting an ambitious green recovery plan for the EU and adopting one for Germany. The present draft of the coal law does not reflect this leadership, nor does it reflect Germany’s important history of leadership on climate and energy over the last 25 years. Now is the time to adjust the coal phase-out law to make it truly consistent with the Paris Agreement – and turn the COVID crisis into an opportunity to accelerate a shift away from coal, breaking out of the politics of inertia.

Notes

(1) We assume a capacity factor of 35% for hard coal plants, and 60% for lignite plants. This is based on 2019 data, and does not take into account the impact of COVID-19 on the estimates for 2020. The projected failure to meet the emission reduction targets in 2020 are also subject to uncertainty.

(2) In a recent report on Germany’s transport sector, we calculated a budget of 9.7 GtCO2 from energy and industry for 2016 to 2050, and with the emissions that occurred in 2016 and 2017 this reduces to 8.1 GtCO2 for 2018-2050.

Header image: German activists protesting the opening of the new coal power plant in Datteln. ©Ende Gelände Hamburg