Evidence from Berlin makes the case for urban green spaces: up to 3°C cooler in a heatwave

As global temperatures continue to rise, the safety and well-being of citizens within urban environments becomes increasingly important. Our recent work in the Berlin-Brandenburg area on adaptation to heat stress hammers home some truths – greener is better.

Share

Just over half of the world’s population live in cities, and with 2023 being the hottest year on record, the cultural melting pots of the world are beginning to feel like they are actually melting. Our recent work in the Berlin-Brandenburg area on adaptation to heat stress hammers home some truths - greener is better. It also points to the ways in which vulnerable populations are already being disadvantaged when it comes to extreme heat.

Cities are particularly vulnerable to heat stress due to the urban heat island effect. Surface sealing, a lack of vegetation, and energy consumption mean that it feels hotter in urban areas than in their natural surrounds. Because urbanisation is on the rise, along with global temperatures, heat stress in cities is expected to further intensify.

Berlin is no exception. Its population is projected to grow about 5% by 2040, with the age group of 65 to 80 year olds to grow faster than younger groups. The average age is expected to rise. And we know that vulnerable population groups, such as 65 and above, are especially at risk due to persistent heat.

"Heat protection is particularly important in an aging society, as high temperatures can exacerbate many diseases, particularly cardiovascular ones. Therefore, climate protection and adaptation also serve the public’s health." - Pankow District Mayor Cordelia Koch

Along with VITO and BUUR (part of Sweco) we set about to understand how stress is already impacting Berlin, and how this will progress at higher levels of warming in the future.

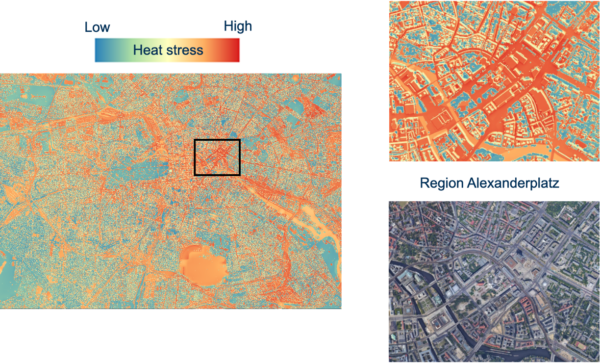

First, it’s clear that extreme heat is something that Berliners are already dealing with at current levels of warming. We can see from our modelling that large, vegetation-free areas like parking lots and building complexes create unfavourable microclimates with high temperatures. Conversely, areas with continuous green canopy and mature urban trees provide the best protection.

The significant temperature difference between sealed and green areas is vividly illustrated in the depiction of Alexanderplatz during the hottest point of a sample day in July 2019 in the middle of a European heatwave. We see that the few parks in the vicinity clearly serve as “cooling” zones.

We found it particularly concerning that some kinds of public commons, namely playgrounds and sports areas, which are where vulnerable populations such as children congregate on sunny days, are often designed as vegetation-free spaces, emerging as heat islands even in densely populated residential areas.

While Berliners have been exposed to rising heat extremes for several years, we can expect that these periods will increase due to the effects of climate change. Currently, the number of tropical nights - where the temperature does not fall below 20°C - in Berlin’s city centre reaches about 15 nights per year. Tropical nights make recovery during heatwaves challenging, particularly for the vulnerable, elderly and children.

By 2050, Berlin’s tropical nights could double to more than 30 nights per year, if we don’t do more to reduce our emissions. But, if we are able to limit warming to 1.5°C, we could also limit this rise to 20-25 tropical nights per year.

Our work on heat stress modelling for Berlin-Brandenburg was based out of the Horizon Europe project, PROVIDE, and funded by the Climate Change Center Berlin-Brandenburg. The data has been integrated into the Climate Risk Dashboard alongside information for 139 other cities.

As global temperatures continue to rise, the safety and well-being of citizens within urban environments becomes increasingly important. The construction of new urban areas and the redevelopment of existing ones must be approached with a strategic focus on integrating local cooling zones. This particularly applies to areas designed for the most vulnerable populations - like playgrounds.

By incorporating these measures into urban planning, cities can not only adapt to the temperature rise but also proactively protect the health and comfort of their residents. The establishment of cooling zones represents a crucial step towards creating resilient and livable cities that can effectively navigate the challenges posed by climate change.