Briefing note on the report on the Structured Expert Dialogue on the 2013-2015 Review

Authors

Share

One of the outcomes of Copenhagen in 2009 was an understanding by Heads of Government that global warming should be held below 2°C and this limit would be reviewed to examine the concerns of the Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Countries (LDCs), who believed a lower global warming limit of 1.5°C would be essential for their survival (see Paragraph 2 of Copenhagen Accord).

This was formalised in 2010, in the Cancun Agreements, where governments agreed to examine the 1.5°C limit in the context of a review that would consider strengthening the long-term global 2°C goal on the basis of the best available scientific knowledge. The review, entitled the 2013 – 2015 Review, began in 2013, with a scientific component called the Structured Expert Dialogue (SED) and a political component called the Joint Contact Group.

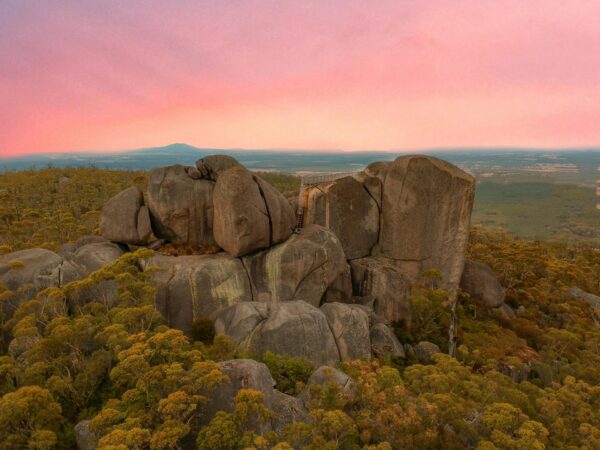

Risks for large parts of the cryosphere (Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets) may increase substantially between 1.5°C and 2°C warming. This image of an Antarctic ice shelf, the floating extension of a seaward glacier, was taken during the 2012 Antarctic campaign of NASA’s Operation IceBridge, a mission that provided data for an ice shelf study indicating that warm ocean waters are melting the ice sheets from underneath.

What is the SED?

The 2013-2015 review was structured around two themes:

- Is the long-term, 2˚C global goal adequate in the light of the ultimate objective of the Convention?

- Is the overall progress towards achieving the long-term global goal, adequate?

In this blog, we focus on the first of the review’s themes, where Article 2 of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) provides the basis for the assessment. Article 2 says (our emphasis):

“The ultimate objective of this Convention and any related legal instruments that the Conference of the Parties may adopt is to achieve, in accordance with the relevant provisions of the Convention, stabilisation of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system. Such a level should be achieved within a time frame sufficient to allow ecosystems to adapt naturally to climate change, to ensure that food production is not threatened and to enable economic development to proceed in a sustainable manner.”

One of the main concerns in establishing the review was to ensure its scientific integrity, which is why governments agreed that the SED would be led by former senior IPCC convening lead authors (1) , would include IPCC findings as one of the main elements of its review, and would provide a forum for open and substantive discussions between experts and governments on the scientific knowledge and evidence-based climate policy formulation. Over the course of the SED’s work, more than 70 experts have participated in the dialogue, including the coordinating lead authors and co-chairs from the latest IPCC AR5 presenting their findings. The final, technical summary was published in May 2015.

This report represents the most comprehensive, up-to-date assessment of the differences between the impacts of climate change at a warming level of 2°C and 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

What are the findings of the Structured Expert Dialogue?

The report finds that the ‘guardrail’ concept, in which up to 2°C of warming is considered safe, is inadequate. In fact, the report confirms significant climate impacts are already occurring at the current level of global warming and additional magnitudes of warming will only increase the risk of severe, pervasive and irreversible impacts.

Consequently, the report confirms that a warming of less than 2 °C would be more preferable – a view that is also shared by the IPCC experts (2) that participated in the SED.

The report has also assessed the differences between a warming level of 1.5°C and 2°C, and concludes that limiting global warming to 1.5 °C would avoid or substantially reduce risk including threats to food production or unique and threatened systems such as coral reefs or many parts of the cryosphere (glaciers, ice sheets of Greenland and Antarctica) and the risk of sea level rise. The report identifies key differences in climate impacts between 1.5°C and 2°C – depicted in Fig .1 (left).

Recent scientific literature (published since the IPCC cut-off deadline) has endorsed the findings by the SED and indicates that:

- Large parts of the cryosphere (Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets), may be much more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change than previously thought and, in particular, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet may be already in an unstable retreat (3,4,5) .

- Tropical coral reefs, one of the most precious and at the same time most vulnerable ecosystems, might be not only threatened by ocean acidification and increased bleaching, but also by increased disease related mortality due to climate change (6).

- There is a substantial increase in climate extremes between 1.5°C and 2°C. For heat extremes, the risk is projected to almost double (7).

While this is not a comprehensive list and large uncertainties remain, what we can say is that there is an emerging scientific picture that tells us that a 2°C limit might be simply too high.

Does a 1.5°C goal makes sense, and can we achieve it?

Clearly, in a time where emissions are on the rise and some claim that even the 2°C target is out of reach already, a call for 1.5°C may seem quixotic. However, if this is what science tells us about “dangerous interference” with the climate system, then we have to stand up to reality and face this challenge.

The SED report has confirmed, once again, that limiting global warming below 2°C is still feasible and comes at “manageable costs,” even without taking potential co-benefits into account. Or as Ottmar Edenhofer, co-chair of the IPCC AR5 Working Group III has couched it: “It doesn’t cost the earth to save the planet.”

The report further confirms that a 1.5°C target is still within reach. The technologies required for the 1.5 °C scenarios are the same as for the 2 °C pathway, but need to be deployed faster, and primary energy demand needs to be reduced earlier – or put another way, energy efficiency must be improved faster. This implies a higher direct mitigation cost than for a likely below 2°C pathway (8,9).

The SED found that fact that there are higher direct mitigation costs for 1.5°C does not determine whether or not this warming limit should be pursued: “…cost implications would not determine whether or not to pursue the 1.5 °C warming limit.” In doing so the SED confirmed the IPCC AR5 finding that it is not possible to simply compare the mitigation costs against avoided impacts -cost-benefit analysis – to conclude whether one target is better than another.

It has to be noted that potential negative side effects of stringent mitigation targets, such as an increased need for bioenergy and the potential risks of increased land-use change as a result, as well as risks arising from negative emissions might be significant. These, however, must be balanced against the substantially reduced impacts of climate change and a range of co-benefits, such as benefits for human health and agriculture due to reduced air pollution. Consequently, the SED report advises governments to “avoid embarking on a pathway that unnecessarily excludes a warming limit below 2°C.”

1.5°C- a question for survival for tropical coral reefs

The SED found that the risk for coral bleaching would become very high under a 2°C warming, which could lead to a near-complete loss of these unique and threatened system globally. The picture shows a colony of the soft coral known as the “bent sea rod” stands bleached on a reef off of Islamorada, Florida.

2°C as a defence line: to be certain to hold warming below 2°C, we should aim for 1.5°C

One aspect of the discussion on emission reduction – or mitigation – pathways that is often overlooked is the actual probability of meeting the 2˚C limit (or goal).

In fact, analyses of mitigation and emissions pathways often assume a 50% probability of holding warming to below 2°C is sufficient. An initial pathway that meets this criteria effectively giving a toss of the coin chance to hold warming to 2°C. A higher probability has been chosen by the IPCC for its main results, where 66% probability pathways for limiting warming below 2°C are summarized in its Summary for Policymakers: in other words the emission limits from those pathways would like to give a one in three chance of exceeding 2°C.

The SED provides some insight on this question when it finds that “Parties would profit from restating the long-term global goal as a ‘defence line’ or ‘buffer zone’, instead of a ‘guardrail’ up to which all would be safe.”

What does “defence line” mean in the light of a substantial scientific uncertainty of the response of the climate system to emission pathways? Is a 50% or 66% chance of staying below 2°C really enough? Wouldn’t one rather increase the odds of not exceeding it, by ramping up climate action to achieve an 80, 85, or 90% probability?

While the SED does not provide information on the specific characteristics of such high-probability emission pathways, the IPCC AR5 and the 2014 UNEP Emissions Gap report, and other recent scientific literature provide guidance on this. We have reviewed the recent literature in a briefing note which shows the different consequences for emission reductions assuming different probabilities of limiting warming (10) and in the shorter term, benchmark emission levels for 2020, 2025 and 2030 consistent with different goals (11). And we find that emission pathways that have a high probability (above 85%) of holding warming below 2°C throughout the 21st century also have a 50% or greater probability of limiting warming below 1.5°C by 2100.

In other words, if we want to be sure (still not 100%) we won’t exceed 2°C, we should instead aim for 1.5°C.

Next steps and implications for the climate negotiations

The joint contact group (JCG) on the Review, which will meet at the UNFCCC sessions in June in Bonn and is tasked to evaluate the outcome of the SED, must ensure that this indispensable source of information is used to advise negotiators on the level of climate action that should guide the Paris agreement – and to advise the COP21 in Paris on the need for strengthening the long-term global goal.

The outcome of the SED provides the scientific support for the use of 1.5°C pathways in the ADP agreement, in particular to guide the ongoing improvement in emission reduction commitments and the assessment of the aggregate impact of the iNDCs. It must be ensured that the 2020 – 2025 pathways in the Paris Agreement do not render achieving the 1.5°C goal infeasible by requiring unrealistic post 2025 decarbonisation rates (9).

In a more general sense, the outcome of the SED report should lead to the climate policy world broadly recognising the rising level of scientific evidence that indicates the 2°C goal is inadequate and that limiting warming below 1.5°C would be substantially safer. For the next round of science assessments of climate change impacts and policy responses the results of the SED point to the need for the IPCC to ensure that the main sets of scenarios to be run by climate modelling groups include very low emission scenarios consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C by 2100.

The SED report calls for more stringent mitigation targets than what are generally discussed in the climate policy arena and must be seen as a call to action for the Paris meeting to fulfil the mandate of the UNFCCC.