What does the Paris 1.5°C limit mean for Australia?

Niklas Roming

Last December in Paris, Australia, along with world governments, agreed to keep warming well below 2˚C and to pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5˚C. What does this mean for Australia’s climate policy and decarbonisation? What would the differences in impacts be for Australia between 1.5˚C and 2˚C of warming? We undertook a study for The Climate Institute to examine these points in detail.

Share

Originally published by RenewEconomy

Australia has signed – and intends to ratify – the Paris Agreement. Achieving this goal requires achieving zero emissions globally by the middle of the 21st century.

Despite having a comparatively small population, Australia’s emissions per capita are very high, making it the 14th largest contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions since 1850 – thus carrying a lot of historical responsibility for the 1°C of global warming the world is already experiencing.

At the same time, Australia’s population is one of the most affluent in the world, in a country with vast potential for renewable energy from wind and solar. Reducing emissions quickly is easy for Australia and is a moral imperative under any consideration of fairness.

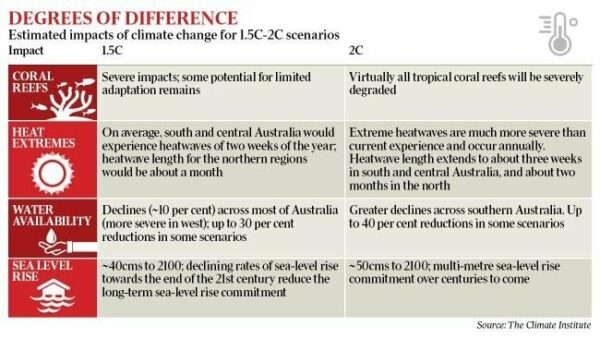

Limiting man-made long-term temperature increase to 1.5°C as agreed in Paris, instead of the previously-agreed 2°C above pre-industrial levels is in Australia’s own interest, we found. It has substantial implications for key climate impacts and indicators.

The continent will be exposed to climate change impacts like sea-level rise, coral reef loss and extreme weather events. All of these effects are already observable today and will be much worse in a 2°C world compared to a 1.5°C world.

For tropical coral reefs, the difference between 1.5°C and 2°C might be decisive in the preservation of reefs. This is a particularly decisive issue for Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, a World Heritage Site, if there is any intention of protecting it.

The difference between 1.5°C and 2°C marks the difference between the upper end of present day climate variability and a new climatic regime in relation to temperature and water-related extremes. In a country already experiencing temperatures exceeding 40°C in its urban centres, this is a very serious reason for concern for human health as well as labour productivity.

In combination with a substantial drying trend projected in particular for southern Australia and in particular the South-West Land Division of Western Australia, this will negatively affect agricultural productivity as well as lead to increased risks of grassland and forest fires.

The reality of Australia’s climate policy does not take any of these considerations into account: its climate pledge submitted to the UNFCCC prior to COP21 in Paris included a greenhouse gas emissions reduction target of 26-28 % below 2005 levels by 2030.

Australia’s actual climate policies, however, would lead to an increase of 27% compared to 2005 levels by 2030 – a lot of this being due to the repeal of the Clean Energy Future Package. Even if Australia was to meet its target, its contribution to climate change abatement would remain very limited.

As part of the process agreed in Paris, governments need to reconsider – and improve – their climate pledges in 2020.

With global emissions targeted to reach zero in 2050 and Australia being responsible for a relatively large share of historical and present day emissions, it needs to set very ambitious targets.

Actual, sector-specific, reduction targets need to be carefully researched, but a few things are clear:

- Australia needs to shift its electricity system towards renewables.

In a country with very high sustainable potential for renewable electricity, especially from solar, wind and geothermal energy, coal still remains Australia’s main energy source of electricity generation. This is partly due to the importance of coal exports for the national income and the already existing infrastructure for coal extraction and transport but, in light of a possible global peak in coal use, it might be wise to reconsider this reliance on resource exports as well.

- Australia needs to decarbonise its transport system with a special focus on urban transport.

Transport sector emissions have been rising over the past decades. Metropolitan transport is relatively easy to decarbonise by shifting from cars to public transport running on renewable electricity. Long-distance transport is more difficult to decarbonise but at least between major urban agglomerations high-speed trains or futuristic concepts like the hyperloop could become viable alternatives to airplanes.

- Australia needs to cut back its emissions from deforestation.

Emissions from Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) make up about a quarter of Australia’s anthropogenic GHG emissions with, mostly from deforestation. The Australian Government projects land use, land use change and forestry emissions projections to 2030/Australian LULUCF emissions projections to 2030.pdf that this will likely continue until 2030 while reforestation, which might counteract, will decrease.

Australia needs to take these emission reduction measures regardless of whether its climate policies were to be in line with limiting global warming to 1.5°C or 2°C. These reductions just need to happen faster to stay under the 1.5°C limit. But with its high standard of living and high public awareness, Australia is very well suited to lead in these transformations instead of a being laggard as until now.