2023 will shape the Loss and Damage fund for years to come – have your say now

Share

COP27 saw an historic win for vulnerable countries already suffering the acute effects of climate change. After 30 years of negotiations, the world’s governments finally agreed to set up a Loss and Damage (L&D) fund to help countries recover from climate devastation.

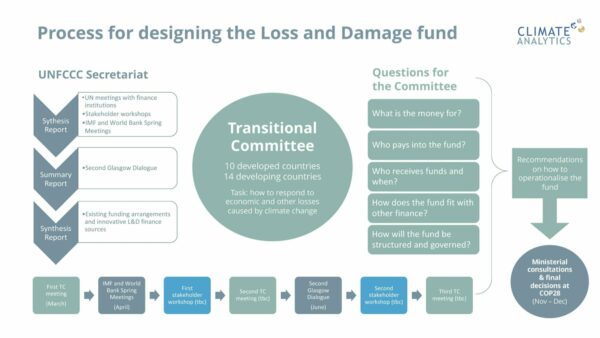

The Summit discussed new funding arrangements and established a Transitional Committee to figure out how to operationalise the L&D fund ahead of COP28. Here’s what to expect from the year ahead.

New funding arrangements agreed at COP27

The L&D fund is part of new funding arrangements agreed at COP27 to help particularly vulnerable countries bounce back from damaging climate events. Exactly what these funding arrangements are and how they link to the L&D fund will be carved out this year. As the fund was agreed as part of a package, it should operate under UNFCCC and Paris Agreement treaties.

The L&D fund is designed to respond to immediate need and so is different from other climate finance, which relies on long applications to specific projects with no means of disbursing funds quickly. Ideally, the L&D fund will kick in when a country requires urgent assistance in the immediate aftermath of an event that causes economic and other losses to help countries get back on their feet.

What will the Transitional Committee do?

The Transitional Committee was set up to look at how the new funding arrangements will work before the next UN climate talks in December (see diagram). Of its 24 members, 14 are from developing countries, including two small island developing states and two least developed countries. The Committee will meet at least three times this year (meeting first in March) to come up with recommendations on how the fund should run. These will be presented at a ministerial meeting in November to prepare the ground ahead of final decisions on the fund at COP28 in Dubai.

To feed into this process, the UNFCCC Secretariat will organise two workshops for institutions working on loss and damage and report their outcomes to the Committee. Elsewhere, the second Glasgow Dialogue will look at how the new funding arrangements and the L&D fund will operate, as well as how to maximise support from non-government actors. The UN Secretary General will also meet with international financial institutions to discuss L&D finance and the topic will be on the agenda at the World Bank and IMF Spring Meetings.

Here are five tricky questions the Transitional Committee will consider:

- What is the money for? Will payments cover the value of lost or damaged assets (language around compensation was deliberately left out of the agreement) or the cost of responding to an event? If the latter, what kind of action counts as an L&D activity? The decision text mentions rehabilitation, recovery and reconstruction, but there’s no detail on what this means and what else might be covered.

- Who pays into the fund? The world’s wealthiest countries will undoubtably have to contribute, but what about other big emitters with large economies like China and Saudi Arabia that are classed as ‘developing’ under UNFCCC rules? Other novel sources of money have been suggested, such as windfall taxes on fossil fuel companies. The question of who pays will likely remain a sticking point throughout the year.

- Who receives funds and when? The decision made at COP27 specifies that the fund should assist developing countries that are particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of climate change. But beyond this broad eligibility criterion, when to disburse finite funds and to whom will be a central question for the Committee.

- Where does the fund fit in with other finance? The question of how to complement and coordinate with other finance structures is important. For example, there is a risk that humanitarian aid could be relabelled L&D funding, even though these funds are already under resourced and are under additional strain from climate change. The Committee is expected to identify exactly where the fund sits within the broader constellation of climate and development finance.

- How will the fund be structured and governed? There could be separate tracks for sudden events like floods verses slow-onset events like sea level rises, or for economic losses like damaged infrastructure verses non-economic impacts like the loss of cultural heritage (which is hard to put a price tag on). The answers to the above questions will need to be reflected in how the fund is structured and governed.

These seemingly technical questions are ultimately political – countries most vulnerable to climate catastrophe and least able to respond have just one year to put forward their ideas and share their perspectives to help shape a fund that truly reaches the people most in need when they need it most.