Extreme heat in Phoenix could make outdoor work ‘impossible’ for nearly half the year – new data

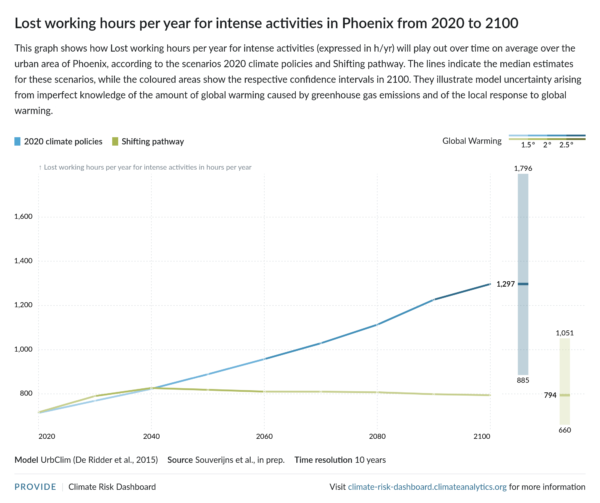

New data shows that if we don’t take more action to limit the effects of global warming, by the year 2100 temperatures in Phoenix will get so high that 1297 hours every year will be considered unsafe for work outdoors.

Share

New data shows that if we don’t take more action to limit the effects of global warming, by the year 2100 temperatures in Phoenix will get so high that 1297 hours every year will be considered unsafe for work outdoors. That’s 162 eight hour work days. This would mean nearly half of the working year could be lost to heat for outdoor work if global warming is allowed to reach 3°C, which is where it's headed under current climate policies. Major sectors that would be affected include construction and tourism.

“Phoenix is already sweltering. Temperature records are being broken again and again, and we’re already seeing increasing deaths from heat,” commented Dr Carl Schleussner, Science Advisor at research organisation Climate Analytics. “The data is telling us that unless we do more to reduce our emissions, extreme heat will decimate working conditions outdoors.”

“The only way to limit our exposure to deadly heat is to reduce our emissions of greenhouse gases. If we do this fast enough we can limit global average warming to close to 1.5°C, which would peak the increase in extreme heat in Phoenix by around 2040, and bring it back towards present levels by 2100. This is 40% below the exposure levels predicted at 3°C of global warming, where global current policies are headed,” said Schleussner.

The limits for safe working conditions under heat stress for ‘intense activities’, such as carrying heavy material, shovelling or sawing, are defined by The International Organization for Standardization. Intense activities are assumed to be affected as soon as wet-bulb globe temperature, which accounts for factors such as temperature, humidity, wind and shading, exceeds 79.9°F (26.6°C). It’s assumed intense activities become impossible when wet-bulb globe temperature reaches 90.7°F (32.6°C).

“We need to be realistic. Just because these temperatures are classified as unsafe doesn’t mean that people aren’t going to get outside and have to work, with potentially devastating consequences for their health,” said Frances Fuller, Director of Climate Analytics North America.

The data is published on the Climate Risk Dashboard, which compares a current policy outlook with a scenario where we are able to reduce emissions enough to limit average global temperature rise to 1.5°C, the goal of the Paris Agreement.

“A key takeaway when we compare a scenario where we limit warming to 1.5°C, and one in which we don’t do more, is that 1.5°C means that in 2100, our children and grandchildren will be living in a climate closer to what we experience today. They will still see extreme heat, but they will be able to manage it. I can’t really imagine what life would be like in the alternative,” Schleussner finished.

The Climate Risk Dashboard includes information on climate impacts in all countries, and 130 cities. It is an output of the PROVIDE project, developed by the research organisation Climate Analytics, and funded from the European Union’s research and innovation programme, HORIZON 2020.